CAMDEN, New Jersey — Florence Sally Horner was born in Trenton on April 16, 1937, to Russell and Ella (Goff) Horner. She had an older half-sister, Susan Swain, born in 1926.

Russell Horner died on March 24, 1943, at age 41, leaving Ella Horner a single mother. Two years later, Sally’s sister married Alvin Charles Panaro.

Sally resided with her mother at 944 Linden St. and attended Northeast Elementary School.

As she approached her 11th birthday, Sally wanted to be a part of a girls club at school. However, the members told her to steal something from the local five-and-dime store to join their group.

In March 1948, Sally stole a notebook from the five-cent counter at the local Woolworths. (A few old newspaper articles say it was June 1948.) A man named Frank La Salle caught Sally stealing and confronted her.

“I am an FBI agent. You’re under arrest,” he said.

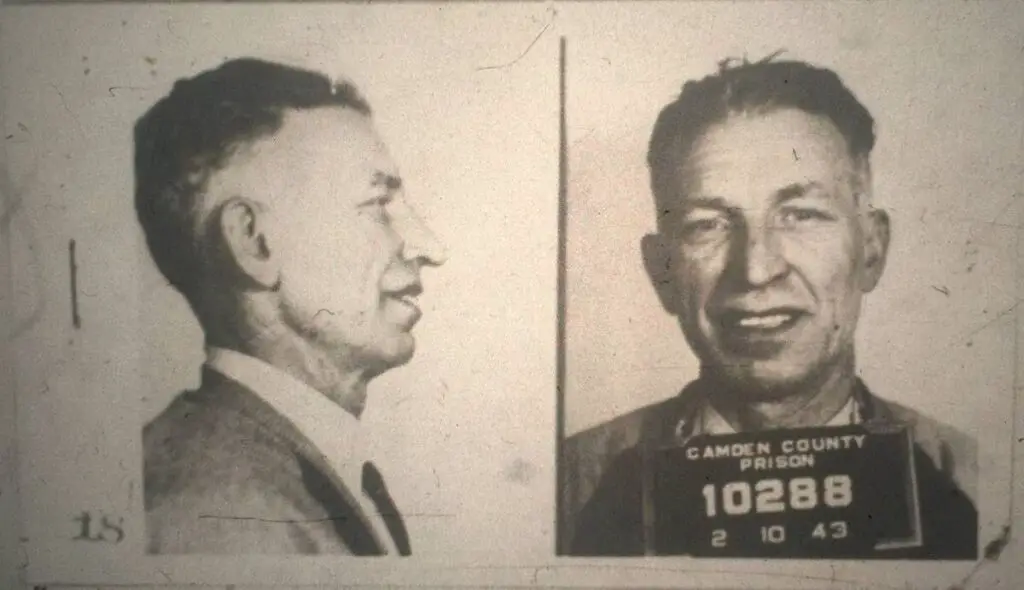

In reality, La Salle was a 50-year-old convicted child rapist, who had recently been “released on parole after serving time for the statutory rape of five girls, ages 12 to 14,” Shelby Vittek wrote in New Jersey Monthly.

La Salle also had previous charges of assault and battery, bigamy, enticing a minor, and violating the Mann Act.

Sally began to cry. La Salle told her the city hall was across the street and threatened to put her in reform school, but he would not do it if she occasionally reported back to him.

La Salle approached Sally again in June 1948.

“He said he would have to take me to Atlantic City because the government insisted I go there. He said it wouldn’t take long to straighten things out. He telephoned my mother and said he was taking some other girls to Atlantic City and would have to take me.”

As told to Santa Clara County Sheriff Howard Hornbuckle by Sally Horner shortly after her rescue, Courier-Post, March 22, 1950.

On June 14, 1948, with Sally’s mother present, Sally boarded a bus in Camden with La Salle. Ella Horner knew La Salle as Frank Warner.

Horner scanned the bus station for the two girls but never saw them, only “Warner.” Regardless, she let Sally board the bus with him.

Sally told Hornbuckle, “I went away with him and a woman about 25 years old. He called her “Miss Robinson” and said she was his secretary and he paid her $90 a week. Instead of Atlantic City, we went to Baltimore. Miss Robinson disappeared, and I never saw her again.”

That night, Sally called her mother, reassuring her she was okay. The following day, Horner received a letter from Sally saying she was staying in a home at 200 Pacific Avenue, Atlantic City. Over the next several weeks, mother and daughter stayed in touch through letters and telephone conversations.

Then, Horner received a letter from Sally that said she and the man were going to Baltimore and a subsequent final letter saying she would no longer write.

La Salle raped Sally on the night they arrived in Baltimore and numerous times afterward. He always carried a gun to keep Sally in line and told her he’d imprison her for theft if she ran away or went home.

According to 1950 newspaper articles, La Salle and Sally remained in Baltimore for eight months, and Sally attended a parochial school.

Horner reported her daughter missing to the Camden police on Aug. 3, 1948, when contact with Sally ceased. Authorities went to Baltimore, but La Salle’s landlady said they were not home. Through the landlady, La Salle learned the police were looking for him, so he took Sally and fled to Dallas, Texas, where they remained for over a year.

Then, in mid-to-late March 1950, Sally was attending a Dallas school when she confided in a “school chum” about intimate relations between her and her “father.” The classmate told her, “what I was doing with him was wrong, and I ought to stop,” Sally later said.

Shortly after, La Salle moved her to San Jose, California, where they stayed in a trailer at a tourist camp.

Throughout her time with La Salle, he never left her side, constantly monitoring everything she did. She never had a moment alone to escape and seek help.

However, three days after arriving in San Jose, La Salle left Sally alone at the trailer for the first time to buy food. She immediately asked a female resident at the camp to use the telephone, and Sally called her mother. Unfortunately, the telephone company disconnected Horner’s phone after she lost her seamstress job weeks before. Sally then dialed her sister, Susan Panaro. Alvin Panaro answered the call, and Sally cried and said, “Send the FBI after me, please.”

Panaro excited beyond belief, insisted Sally tell him her exact location, and she did. Then, he gave the phone to his wife, and the sisters spoke for the first time in 21 months.

“Tell mother I’m okay and don’t worry. I want to come home. I’ve been afraid to call before,” Sally cried.

Susan Panaro told her little sister to stay at the camp until the police arrived. She and Panaro called the Camden detectives working on Sally’s abduction, who immediately telephoned the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office and the San Jose office of the FBI. The detectives relayed the information about Sally’s abduction and told them to use caution when approaching La Salle.

Shortly after, three Clara County deputies zoomed into the camp and rescued Sally.

At 1 p.m. Pacific time, deputies and FBI agents waited discreetly for La Salle to exit a city bus and walk to the trailer he and Sally resided. Police quickly surrounded him, and he surrendered quietly.

Camden County Prosecutor Mitchell Cohen and two detectives immediately flew to California.

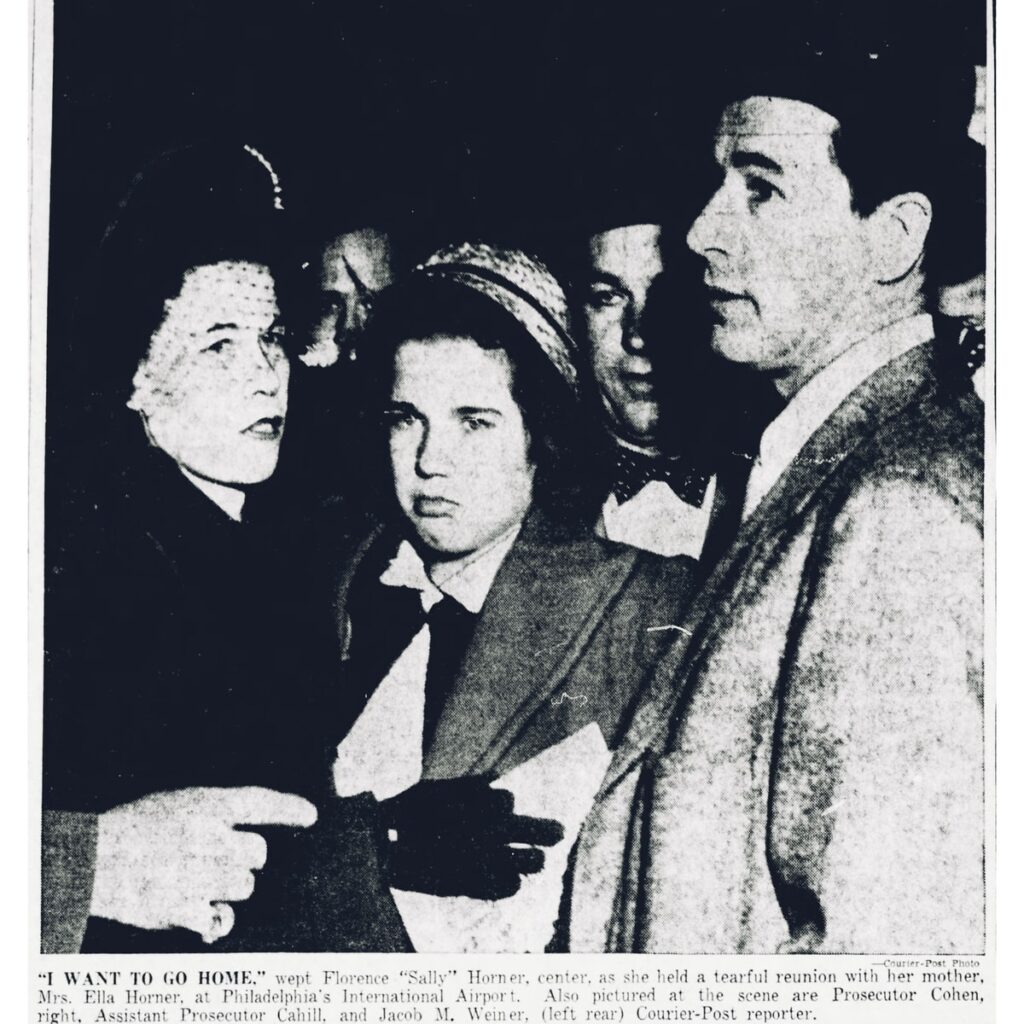

Around 11:30 p.m. on March 31, 1950, Cohen, Sally, and the two detectives, arrived at Philidelphia International Airport, where Horner anxiously awaited the arrival of her daughter.

After Sally exited the aircraft, she flew into her mother’s arms, and the pair hugged each other and sobbed. Sally’s sister, brother-in-law, niece, and aunt were also at the tearful reunion.

Then, police whisked Sally away to Camden County Children’s Shelter, where she remained in protective custody for a short period.

Meanwhile, La Salle and two investigators flew into Philadelphia the following morning and returned to Camden.

La Salle was charged with kidnapping and violating the Mann Act, taking a minor across state lines for “immoral purposes.” According to The Daily Record, he pleaded guilty, and County Judge Rocco Palese sentenced him to 30-35 years in prison in April 1950.

After Sally’s rescue, she tried to return to somewhat everyday life and went back to school. According to author Sarah Weinman, who wrote a book (affiliate link) on Sally in 2018, “The family discouraged discussion of her kidnapping, and she almost never spoke of her ordeal with anyone.”

However classmates of Sally knew what she had gone through, but instead of being kind and understanding, they bullied her and called her all kinds of horrific names. But through all that, she befriended Carol Taylor, and the two became inseparable best friends.

Unfortunately, tragedy would strike again as fate dealt another vicious blow to the Horner family.

On Aug. 18, 1952, Sally, 15, was killed in a car accident in Woodbine, New York. Sally was in a car driven by 20-year-old Edward Baker; he survived the crash.

When Baker met Sally, he thought she was 18. He did not know before her death that she had been abducted. Regardless, according to Weinman, her death affected him for the remainder of his life.

Shortly after Sally’s death, La Salle sought release from state prison, claiming he was “illegally convicted,” however, the State Supreme Court denied his appeal for a writ of habeas corpus.

In July 1956, La Salle applied to have his sentence commuted, but it was also denied. He died in prison from arteriosclerotic heart disease at age 69 on March 22, 1969, 19 years after Sally’s rescue.

“Lolita,” (affiliate link), written by Russian author Vladimir Nabokov, debuted in the U.S. in 1958. Though he never admitted it, Nabokov likely based his story on Sally’s abduction.

In his book, Nabokov tells the story of middle-aged Humbert Humbert and his obsession and sexual relationship with 12-year-old Dolores “Dolly’ Haze.

“Lolita” became Nabokov’s most famous and controversial book during his career. It was also his “most difficult book” but gave him “the most pleasurable afterglow—perhaps because it is the purest of all, the most abstract and carefully contrived,” he said in a 1964 interview with Life magazine per Leland De la Durantaye’s 2007 book, “Style is Matter: The Moral Art of Vladimir Nabokov.” (affiliate link)

Sally’s death must have devastated her mother and sister. How unfair to have lost Sally during the girls’ two-year absence only to see the child die two years later.

But life must go on, people say.

Horner married Arthur Burkett in 1965. However, he passed away in 1970 at age 58. Horner lived a long life and died on May 27, 1998, at age 91.

Sally’s sister, Susan Panaro, died at age 85 on Aug. 1, 2012. Per her obituary, she was “a longtime resident of the Roebling-Florence area and then in Browns Mills for 20 years before entering Marcella. She was a homemaker, but in her earlier years, she worked at her in-law’s business, Panaro’s Greenhouses, in Florence.”

Her husband, Alvin Panaro, followed her in death on Feb. 25, 2016, at age 91.

Shortly after Sally’s abduction in 1948, Sally’s niece, Diana, was born. Diana was 19 months old when Sally returned home. Diana passed away on Sept. 21, 2021, at age 73.

Sally also has a nephew she never met, Brian Panaro. He and his wife, Patty, reside in New Jersey. Their son, Anthony Brian Panaro, died on Dec. 22, 2020, at age 26.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

Even though this is a solved case, I wanted to tell Sally’s story after seeing it on TikTok. I plan to cover more solved cases in the future.

I did not use Weinman’s book as a source because I have not read it. However, it is on my reading list, so I might add new information once I read the book. I read that her book has additional info not found elsewhere, so we’ll see.

To go through what Sally endured for 21 months, only to die two years later in a horrible car crash, is an injustice in itself. Fate was not kind to her, and she deserved to live to a ripe old age.

I also wrote about her because people refer to her in articles and books as the “Real Lolita.” Because of Nabokov’s book, “Lolita” is now used to describe “a precociously seductive girl.”

However, I hate the name “Lolita” because I will forever think of that human garbage, Amy Fisher, aka “The Long Island Lolita,” whenever I see or hear it. Fisher was 17 when she seduced Joey Buttafuoco and shot his wife, Mary, and later received a slap-on-the-wrist prison sentence after accepting a lame plea deal.

Fisher was NOT a victim. She obsessively pursued and seduced 35-year-old Buttofuoco and admitted it. When he broke things off, she went ballistic. Fisher is a vile human being who profited for years off her relationship with him and her attempt to kill his wife.

Sally had no choice with La Salle and was only 11 years old when he abducted her. Sally never talked about what happened to her, and I can guarantee that if she had lived a long life, she would never have written a book or profited in other ways from her forced time with La Salle.