It was 44 years ago yesterday when a Scottish teenager lost her life in a brutal and senseless murder. It was a crime that enraged citizens and demanded swift justice. However, the quick and illegal arrest of an intellectually disabled man later became a pivotal point in the trial.

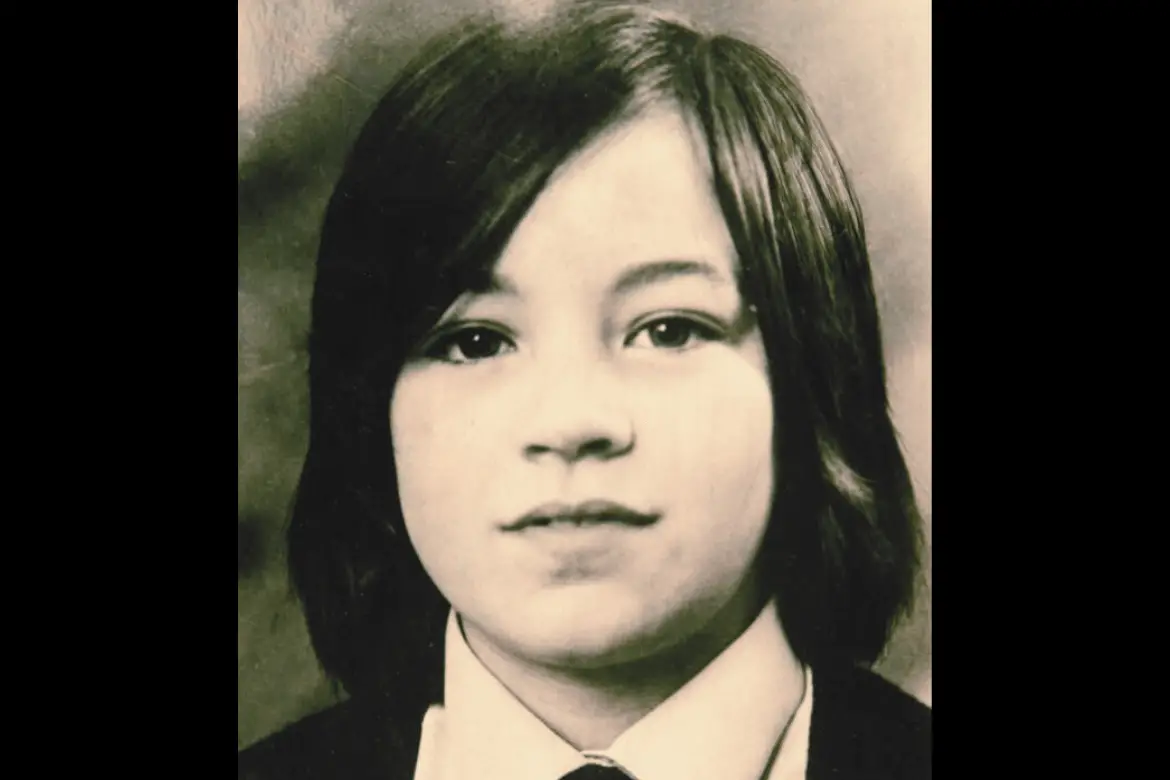

Murder of Tracy Main

Thomas and Dorothy Main lived on the second floor of a tower block home in Norfolk Court, Gorbals, Glasgow, Scotland.

On Tuesday, February 5, 1980, their daughter Tracy, 13, had a day off from school. Her mother returned home from work, noticed the apartment door open, and felt something was wrong. Dorothy went to a next-door neighbor for help, and both entered the apartment. They discovered Tracy’s bloody body on the settee in the living room; her pants pulled down to her knees.

An autopsy showed Tracy’s killer had stabbed her seven times in the chest. They also had put a hand over her mouth to stifle her screams. Despite her pants pulled down, there was no evidence of sexual assault.

Arrest of Thomas Docherty

The public was enraged over Tracy’s gruesome murder and put pressure on the police to make a quick arrest.

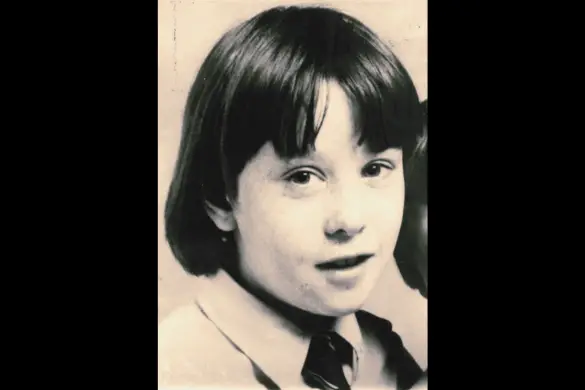

Residents at Norfolk Court directed the police to Thomas Docherty, a 43-year-old man with the mental capacity of an 8-year-old child. Docherty lived next door to the Mains with his 73-year-old common-law wife.

Neighbors called him the “Creeper,” (Sylvester 2020) and told Glasgow police about Docherty’s “furtive behavior & bizarre appearance.”

Immediately, police interviewed Docherty, and he admitted to knowing Tracy. He also described the position of her body and revealed the number of times her killer had stabbed her. That caught the attention of Detective Chief Inspector (DCI) Leslie Brown Detectives because the police never released the number of stab wounds to the public. DCI Brown decided he had enough evidence to arrest Docherty for Tracy’s murder.

Docherty was appointed attorney Joseph Beltrami and Q.C. (Queen’s Counsel) Hugh Morton.

A few hours after Docherty’s arrest, Beltrami had his first consultation with Docherty at the Craigie Street Police Office on Glasgow’s south side. The station shut down in 1990, and the building was recently converted into apartments.

Authorities later detained their suspect at HMP Prison Barlinnie, where Beltrami had several meetings with Docherty and had doubts about his client’s guilt.

The murder occurred several years before the birth of DNA testing when police relied mainly on fingerprints and eyewitness accounts. Still, investigators had no physical evidence linking Docherty to the murder, and there were no witnesses to the crime.

Beltrami realized his client did not know why he was in jail. Nor did he know that police had charged him with Tracy’s murder. However, two psychiatrists examined Docherty and deemed him fit to stand trial, although Beltrami disagreed with the diagnosis due to Docherty’s disability. But if his client did not stand trial, Docherty likely would have been sent to the State Hospital at Carstairs for the remainder of his life.

Beltrami believed his client was innocent. However, he needed to explain how Docherty knew the number of stab wounds Tracy received. Docherty told him he had seen a news broadcast of the murder. After that, Beltrami requested copies of coverage from BBC and Scotland’s STV. He discovered one STV news anchor had said Tracy was stabbed “several” times. Due to Docherty’s low intelligence, Beltrami believed his client might have misheard the broadcaster, thinking the man said “seven.” It was plausible, after all, because they both begin with the same four letters.

Shocking Discovery

Investigators thought they had the smoking gun with Docherty’s statement regarding the seven stab wounds. But luck was on Beltrami’s side.

Preparing for the trial, Beltrami and Morton made a shocking discovery. Similar to Miranda Rights in the U.S., a person arrested in the U.K. has the “right to remain silent,” and the police must caution them of this right.

Beltrami and Morton read DCI Brown’s statement and discovered that DCI Brown had failed to warn Docherty of his right to remain silent. If that were true, “any trial would have to be stopped once that revelation was made in court and their client allowed to walk free.” (Sylvester)

Beltrami and Morton examined DCI Brown’s notebook and noticed the investigator did not mention Docherty’s right to remain silent. Which meant anything Docherty said after his arrest, including the number of stab wounds, was inadmissible in court.

However, Beltrami was worried.

“I could not allow him to walk the streets just now because it may be felt by some people that he has been acquitted on a technicality,” he said in 1980.

He briefly thought to exclude the “caution error” and let the facts come out in court. But Morton disagreed and told Beltrami to cross-examine DCI Brown. (Sylvester)

The Trial of Thomas Docherty

The short murder trial took place a few months after Tracy’s murder. Dorothy Main testified on the first day about acquiring the neighbor’s help after finding the apartment door open and her daughter’s body on the settee.

The prosecution presented the jury with media coverage transcripts of the murder to prove news channels said nothing about the seven stab wounds. Nevertheless, Beltrami and Morton had the ball in their court.

DCI Brown testified that he verbally cautioned Docherty on his right to remain silent in front of his superior, Detective Superintendent Ian Smith.

Morton objected, pointing out Brown was wrong. Lord Cowie Brown cleared the court and met with the attorneys during a two-hour hearing in which DCI Brown admitted he had not written the caution down correctly. However, he insisted he verbally advised Docherty of his right to remain silent. (Sylvester)

Smith admitted that he wrote down what Brown said but said his subordinate did not cite the right to remain silent in the report.

Lord Brown called the jury back and explained the issue regarding the caution. The prosecution withdrew the murder charge against Docherty, and the jury acquitted Docherty on a technicality.

Beltrami: “I am disappointed that the trial did not go the full distance because I was sure he would be acquitted on the evidence. At no time — and I have had many meetings with Mr. Docherty — did I feel he had anything to do with this dreadful murder.”

Public Fury

The public had already convicted Docherty of Tracy’s murder. They were outraged at his acquittal and waited for Docherty to exit the courthouse like a bloodthirsty lynch mob. Beltrami learned that a local bookmaker even put a contract killing out on Docherty, and he knew his client could never return home.

Therefore, Beltrami requested authorities smuggle Docherty out of court and transport him to a police station for protection. His client stayed there for two days. He subsequently went voluntarily to the State Hospital in Carstairs as a patient for a month.

Docherty later lived in a social work hostel in an undisclosed location and never returned to Glasgow. It is unknown whether he is still alive.

Docherty’s Guilt is Questionable

DCI Brown wrote a book in 2005 on Tracy’s murder and stated that “they may have got the wrong man.” (Sylvester)

Detectives focused entirely on Docherty as the culprit, and it appears as if they did not correctly investigate Tracy’s murder.

What evidence did they acquire from the Main’s apartment? The door was open, but did investigators find evidence of forced entry, such as damage to the door itself? Did they collect any fibers?

It stands to reason that if Docherty had the mental capacity of an 8-year-old child, he likely did not know what sex was or even understood what that word meant.

As Docherty allegedly knew the number of stab wounds and the position of Tracy’s body, the investigators could have asked him leading questions to get a confession.

Police only questioned him after his neighbors alerted them. There is no mention of police interviewing any other neighbor as a suspect, but there is little public information on Tracy’s murder.

It is strange that Dorothy immediately sensed something was wrong based solely on the apartment door ajar. Mother’s intuition? Maybe. But we do not know the exact time she returned home. Furthermore, why didn’t she call out for Tracy first or think that Tracy left it open?

It is the opinion of this author that Tracy knew her killer and that she might have been slain following an argument.

There could be a few reasons why the killer did not sexually assault Tracy.

The murderer was a female and staged the scene to make it appear as if Tracy had been sexually assaulted.

The killer could have been interrupted by a knock on the door, or her screams prevented him from doing anything further. He panicked and killed her. Maybe the killer could not perform because she fought back.

Maybe the killer was a fellow student who liked her, had no school that day, and knew Tracy was home alone.

The positioning of her body – slumped on the settee – suggests she did not fear her killer and that they might have had a conversation prior to the attack.

Similar Case

Three years after Tracy Main’s murder, another girl, also named Tracey, was killed.

Tracey Waters, 11, vanished from Johnstone, Scotland, about 14 miles west of Glasgow, on Valentine’s Day 1983. She left her home on Craigview Avenue to go to a youth club but never made it.

According to the Daily Record, the following day, police recovered her beaten body under a bush in someone’s backyard on Shanks Crescent, a mile from Tracey’s home. The killer had strangled her. Investigators believe something or someone disturbed the killer before he could sexually assault Tracey.

Investigators and Tracey’s family believe Tracy’s maternal uncle, Adam McDermott, killed her. He vanished in 2001.

The similarities between the two murders are eerily similar. We have two girls, similar in appearance and close in age, with the same name. Both children were brutally murdered and not sexually assaulted in February, three years apart. In both cases, investigators zoomed in on specific suspects, arrested both men and did not arrest any other suspects.

While the cause of death distinguishes one from the other, it is wild the police never mentioned a possible link, at least none this author could find.

Aftermath

Newspapers in the U.K. in 1980 barely covered Tracy’s murder when it occurred. Several papers only had a small blurb the day after the murder and another tiny blurb following Docherty’s arrest. Nothing more until June 1980, after the acquittal, and no reports until 2020. Shockingly, newspapers did not consider the brutal murder of a 13-year-old girl was newsworthy, it seems.

It’s unclear where Tracy’s parents are today or if they are still alive. Barely any information could be found on the family.

Beltrami wrote “The Defender, Tales of the Suspected” in 1988 on his client’s unfair ordeal.

DCI Brown wrote a memoir in 2005 titled “Glasgow Crimefighter,” in which he mentions Tracy’s murder and the possibility that Docherty might have been innocent, as discussed above. Brown died in 2019.

Tracy Main’s murder remains officially unsolved. The U.K. has a double jeopardy law in which a defendant cannot be tried twice for the same crime unless new evidence is presented.

Part 10 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (the 2003 Act) reforms the law relating to double jeopardy by permitting retrials in respect of a number of very serious offenses where new and compelling evidence has come to light. Previously, the law did not permit a person acquitted or convicted of an offense to be retried for that same offense. – The Crown Prosecution Service

Police made a public appeal for information on Tracy’s murder in 2020.

Detective Chief Superintendent Laura Thomson: “The death of Tracy Main is considered an unresolved murder, and these cases are never closed by Police Scotland.

“Should any new information be received, detectives in our Homicide and Governance Review team will thoroughly assess this and investigate further, wherever necessary.”

Sources

“Detectives Error Frees Man Over Child’s Murder.” The Daily Telegraph (London), June 4, 1980.

“‘Right to Silence’ Omission Ends Murder Trial.” The Guardian (London), June 4, 1980.

Articles by Norman Sylvester:

“Appeal Over Cold Case Glasgow Murder of Tracy Main.” The Glasgow Times. December 8, 2020. https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/news/18928522.appeal-cold-case-glasgow-murder-tracy-main/ (Accessed January 12, 2024)

“Glasgow Crime Stories: The Murder of Tracy Main.” The Glasgow Times, December 8, 2020. https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/lifestyle/18928598.glasgow-crime-stories-murder-tracy-main/ (Accessed January 12, 2024)