Samuel Augustino Buffington, Jr. was born in Chicago, Illinois, on February 8, 1907, to Samuel Augustino Buffington, Sr., and Margaret A. Buffington.

Buffington Sr. founded the Chicago Telephone Supply Company in 1908. He was also president of the Land Company of North America and Giant Construction, based in New Chicago, Texas. He died on Samuel’s fourth birthday, February 8, 1911, from inflammatory rheumatism at age 38.

Margaret was pregnant with their second child and gave birth to another son, Hugh Hodge Buffington, on May 15, 1911. She later married Charles F. Pinkham, a meat inspector in the stockyards.

Samuel and his family lived in a second-floor apartment in Chicago’s Hyde Park at 1428 East 65th Street. Samuel was a high school student and an eagle scout with Boy Scouts Troop 514, in which Samuel had won honors for expert knot-tying. He also faithfully attended Sunday School at church.

At 3 p.m., on October 2, 1921, Samuel’s mother, stepfather, and brother went for a Sunday drive. Samuel stayed home and read an adventurous story called “The Last Lap.”

When the family returned at 6 p.m., they noticed Samuel’s absence but did not think much of it. They thought he might have gone to a friend’s house or decided to play outside somewhere. About half an hour later, Margaret entered her son’s bedroom and found Samuel dead, hanging in his closet.

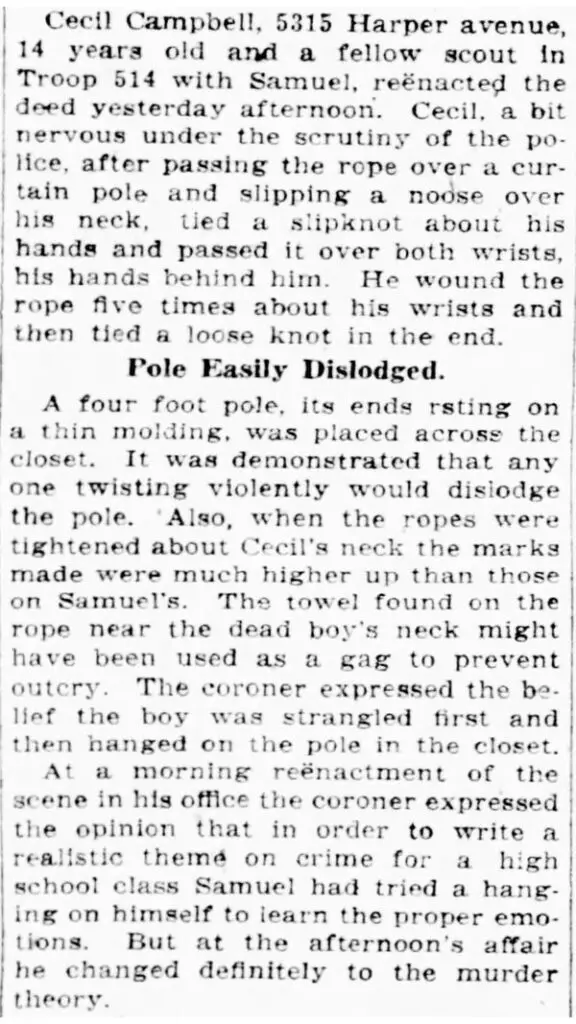

A Boy Scouts pole had been placed on brackets on the closet wall. One end of a rope was tied to the bar, and the other formed a noose. It was the same rope Samuel had used in the knot-tying contests. A rag was placed between his neck and the rope.

Samuel’s hands were tied behind his back. Per the Chicago tribune, “Each wrist had been tied separately in a manner with which the boy was familiar,” having demonstrated on his brother Hugo about a week before his death.

Margaret called the Woodlawn police station. Upon first glance, it looked like Samuel had committed suicide. Officers briefly examined the body when they arrived and found no other injuries. Then, they cut the boy’s body down and the ropes from his hands, which did not sit well with coroner Dr. Joseph Springer upon his arrival. He could not ascertain whether the boy had been alone or someone else had tied the knots.

Investigators found no motive for Samuel to kill himself. His parents said he was in high spirits when they left for their drive.

Margaret and the police theorized someone murdered Samuel, but his stepfather disagreed. Pinkham believed his stepson tied himself up to see if he could extricate himself, but something went wrong. When he struggled to free himself, the rope tightened around his neck, and he strangled himself.

Police questioned Pinkham and Samuel’s mother and learned Buffington Sr. had left $60,000 in cash and real estate in a trust fund for Samuel, which could have been a motive for murder. The amount had dwindled to about $21,000 by the end of October 1921.

Detectives also questioned Samuel’s scoutmaster S.H. Giesy. He explained the way the ropes were tied around Samuel’s hands was “not such as Boy Scouts employ.” His statement further contributed to the murder theory.

They also interviewed Mrs. Mary Friede, 1126 East 47th Street. The Pinkhams had visited her on their drive, but what she told them is unclear as local newspapers did not mention the contents of her police statement.

Coroner Peter M. Hoffman performed the autopsy and ruled the cause of death as “strangulation by hanging,” disproving someone had tied Samuel up and murdered the boy outside the home. However, he still did not know whether Samuel tied his hands or another person did, Hoffman said.

Hoffman first reenacted the hanging on October 5, 1921, but could not determine if his death was accidental or murder. Two days later, he did it again, but this time he had help from 14-year-old Cecil Campbell, a scout with Samuel’s Boy Scouts troop.

Samuel’s mother supported the murder theory, but all she would say for a possible motive was, “He might have known something that somebody didn’t want him to tell.” Pinkham maintained the boy accidentally hung himself.

At an inquiry held on October 11, 1921, Hoffman extensively questioned Margaret and her husband, several physicians, and other witnesses. He determined someone, possibly a “moron,” murdered Samuel. Hoffman said the boy had been dead approximately two hours before his mother found his body. He also determined someone had knocked Samuel unconscious and did not strangle him first. The killer then hung the boy on the rope alive, making his death look like suicide.

In late October 1921, Margaret offered a $1,000 reward for information leading to Samuel’s killer’s arrest. However, no one came forward.

Another case might have been connected to Samuel’s.

Edward Knaus, 14, was a cowboy fan and had several homemade lassos. Neighbors often watched him outside, entertaining himself by lassoing the neighborhood dogs.

On October 6, 1921, four days after Samuel’s death, Edward visited his father’s barber shop and was in a good mood. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary during the visit. He returned to the family residence at 4012 N. Richmond Street. Sometime later, his 11-year-old sister Loretta entered the basement to get clothespins and found Edward dead, hanging from a beam.

The Chicago Tribune reported, “Around the neck was stretched a noose, and the rope, after passing through a ceiling hook, returned and was tied to the boys’ waist. An overturned box lay close at hand.”

Loretta immediately called for her older brother, Walter Knaus, who cut down Edward and carried his body to the backyard. A police officer lived across the street and tried to revive Edward, but it was useless. Firefighters arrived and used a pulmotor, but Edward was dead.

Over a month later, the mother of Charles Willison, Jr., 18, discovered Willison dead in their home at 5041 Grand Boulevard (now King Drive). Willison was in the bathroom. When he never came out, his mother opened the door and found her son hanging from an army belt attached to a pipe. The Willisons lived about three miles from Samuel.

At Margaret’s insistence, the assistant state’s attorney reopened the investigation into his death in June 1922. She reportedly gave new evidence regarding her son’s mysterious death.

“The true story, if it ever becomes known, will read like a dime novel,” Margaret said. Local media never reported anything more on that investigation, and nobody knew what Margaret’s cryptic statement meant.