PICAYUNE, Miss. — The 1980s were full of weird clothes (parachute pants, need I say more?) and hairstyles, breakdancing, fantastic music, and movies I still love to watch today. It was a great decade to be a kid and a much better time than now, no doubt.

My friends and I jammed to Bon Jovi, Guns ‘N Roses, Motley Crue, Poison, and Skid Row songs. And though we would never admit it in a million years, my best friend and I secretly loved Debbie Gibson and New Kids on the Block.

Great movies such as “Back to the Future,” “E.T.,” Footloose” (the only version worth watching), “Karate Kid,” and “The Breakfast Club” played in theaters.

Girls wore their hair teased on top with tons of hairspray (Aqua Net, I’m looking at you), and the “cool” boys wore theirs long.

We cruised the streets with the radio blaring and chatted with friends on the town square.

In August 1989, I was 19 and living with my best friend in a single-wide trailer in our small Illinois hometown. I worked at a local department store while she had a part-time job in a nursing home. We were having the time of our lives hanging out with friends and drinking alcohol like there was no tomorrow. We were young (and stupid) with few responsibilities and sheltered by small-town living to the evil in this world.

For some of us, 1989 was the conclusion to one of the best decades ever and the beginning of adulthood. For others, it was the end of lives taken too soon.

Undoubtedly one of the most talked-about and media-covered murder cases in U.S. history occurred on Aug. 20, 1989, when Lyle and Erik Menendez shot and killed their parents in their Beverly Hills home, citing physical and sexual abuse as the motive.

The following day, another murder happened in small-town Mississippi that barely received any coverage and reeks of a police cover-up with a splash of Dixie Mafia. You know, my kind of case to cover.

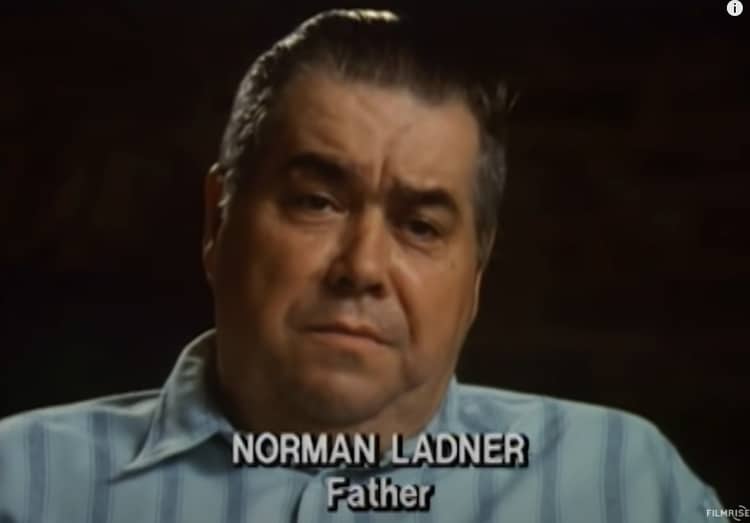

Born on May 29, 1972, Norman Charles Ladner was the third child and eldest son of Norman Ladner Sr. and Charlette Ladner. He had three brothers and three sisters.

Norman, 17, was a senior in high school, dependable, kind, outgoing, responsible, and close to his family. He loved fishing, hunting, and nature and was a skilled craftsman with his own workshop in the family barn. Norman’s parents owned a country grocery store where he worked as a clerk.

The teenager spent summer days exploring his family’s 122-acre property outside Picayune, Mississippi. The property was fenced on all four sides, and at least 60 acres were timber and woods. Norman knew it well and had walked it numerous times.

After exploring or hunting, he would almost always return to the store around 7 p.m. to help his parents restock the coolers and mop and sweep the floors. On occasion, Norman would show up closer to 7:30 p.m. but never later. He was very punctual.

On Monday, Aug. 21, 1989, his father started to worry when Norman had not shown up at the store by 7:00 p.m. Ladner drove home to see if Norman was in his shop, but the boy was not there. Then he thought perhaps Norman became lost or injured in the woods, so he and a few friends started searching the property.

Charlette Ladner helped in the search to some extent but decided to wait for her son at the store. She believed if he had been lost or injured, he would return to the store first.

During the search, Ladner found Norman lying on the ground in the woods.

In a 1990 segment on “Unsolved Mysteries,” Ladner said, “I knelt down by him and felt that he was cold, so I knew he had been dead for a while.” Norman had a single gunshot wound to the head.

Ladner stayed with his son until authorities came. A county deputy drove to the store and informed Charlette Ladner that her son was dead. Soon after, the fight for justice began.

Pearl River County Sheriff Ulmer Lorance Lumpkin arrived at the scene around 10 p.m. and cordoned off the area to begin his investigation.

“Foul play is the first thing I normally address in the course of an investigation. I ruled it out in this instance because I saw nothing there to indicate that,” Lumpkin said in 1990.

“At first I thought it might’ve been an accident. It looked as though he might have been in a tree nearby and subsequently fallen out of the tree and the gun discharged.”

Pearl River County Coroner Johnny Stafford, along with two deputies, strolled into Ladner’s store two days after his son’s death and told him he was 90% certain Norman’s death was an accidental shooting.

Norman’s parents were shocked when Stafford ultimately ruled his death a SUICIDE. He concluded the teen died from a close contact wound that entered his right temple and exited his left. The case was closed and never reopened.

The Ladners did not believe Norman committed suicide. He was happy and not depressed.

Norman’s wallet containing $140 was missing, and the autopsy showed Norman had a 1 ¼”-long laceration on the crown of his head. Stafford claimed he had found a jagged root at the scene with blood on it and believed it had caused the laceration.

Ladner called bullshit on Stafford’s claim because he believed Norman would have fallen backward when he was shot. Therefore, the laceration would have been on the back or side of Norman’s head.

He and his wife tried several times to get Sheriff Lumpkin to reopen their son’s case, but Lumpkin refused each time.

Charlette Ladner knew her son did not commit suicide and believed his death was accidental until she and her husband started their own investigation. They sifted through blood and tissue at the crime scene in an attempt to find the bullet. They found it about two inches in the ground where Norman’s head had been.

“We found a bullet that was longer than a bullet that Norman’s gun would hold. The chamber was not bored out for the length of that bullet.

“And it had dried blood and hair when we examined it under the magnifying glass. The bullet was intact and had a slight twist and knick on it,” Ladner said.

The Ladners concluded that someone had struck Norman on the head and shot him from standing position. They took the bullet to Lumpkin, but he did not believe it was the one that killed Norman, “mainly because we feel that he was standing at the time the gun was fired. And if that being the case, it would not have been in the ground underneath his head,” Lumpkin said.

Lumpkin then gave some lame-ass story that because the police did not find the bullet, there was no way they could prove it was the one that killed Norman.

Ladner said authorities never looked for the bullet. Lumpkin dismissed the bullet found and insisted Norman committed suicide.

“They [police] never fingerprinted the gun. They cannot say that his gun was the weapon that was used to kill him,” said Ladner.

Ladner sent the bullet to a state ballistics expert. However, the expert could not determine if it was fired from Norman’s rifle. Here’s the interesting part. When the expert returned the bullet to Norman’s parents, they realized it was not the same bullet they had found in the woods. WTF?

The Ladners made frequent visits to the coroner’s office. On one visit three weeks after Norman’s death, Charlette Ladner was approached by a man who said he wanted to discuss her son’s case. She agreed and stepped away to speak with him, out of earshot from her husband.

She stated on “Unsolved Mysteries” that the mystery man said, “Mrs. Ladner, don’t open this case up. You have other children. I suggest you raise them for your own good. You’ll never find the person that killed your son.” And then the man left.

The threat did not deter the Ladners from seeking the truth. Ladner made another trip to the crime scene, and about 300 yards from where his son’s body was found, discovered a strange radio-like homemade device hanging in a tree.

Ladner felt the device was potential evidence and took the object to Sheriff Lumpkin, who, of course, dismissed it and insisted Norman committed suicide and that his parents could not accept it.

A neighbor of the Ladners put them in contact with a retired DEA agent who lived nearby. The DEA agent knew what the strange device was. He said airplanes carrying narcotics would fly over an area, and the device would transmit a low range signal, alerting the pilot where to drop the shipment of drugs.

Ladner believed his son might have come across someone picking up a shipment of drugs on their land and that Norman recognized the person or persons involved and was killed.

That theory led some people to believe members of the Dixie Mafia might have been responsible for Norman Ladner’s death and that Lumpkin was their right-hand man.

Before becoming sheriff, Lumpkin was the police chief for the Picayune Police Department and then a Pearl River County deputy.

When Lumpkin was elected sheriff in 1985 at the age of 36, he said, “I intend to do exactly what I set out to do, and that is restore credibility to the office. I intend to be the sheriff for everybody without prejudice.”

Cue serious eye-rolling. Sir, I believe you lied.

The Hattiesburg American reported that “Lumpkin garnered 54.9% of the more than 10,000 votes.” I’m sure it didn’t hurt anything that his father was president of the Pearl River County Board of Supervisors.

The rumor mill says Lumpkin was a dirty cop who worked for the Dixie Mafia, albeit never proven. Nearly a year after Norman’s death, Lumpkin’s residence on Inside Road was heavily damaged in a fire around 10:45 p.m. on July 21, 1990. No one was injured in the fire, and there is little information on the circumstances.

I could not find anything more on this, but my first thought: who did he piss off? And where was his home in conjunction with the Ladner property?

On Tuesday, Oct. 8, 1991, Democratic nominee Lawrence Holliday defeated incumbent Lumpkin, 5,585 votes to 4,098 in the Democratic primary runoff, the Hattiesburg American reported on October 9, 1991. One year later, Lumpkin was arrested along with 36 others in a dog fight raid. He died on December 6, 2007, at age 58.

According to the FBI, the Dixie Mafia is “a loose confederation of thugs and crooks who conducted their criminal activity in the Southeastern United States.”

The Orlando Sentinel reported in 1992 that “Dixie Mafia members engage in just about any criminal enterprise with a profit: gambling, drugs, prostitution, bank robbery, murder, arson, extortion, mail fraud. They are sort of an anything-for-a-buck gang.”

The Dixie Mafia has no connection to the Sicilian mafia, a hierarchy-based organization with dons and godfathers. Dixie Mafia recruited violent criminals who were not afraid to get their hands dirty. Many worked inside prisons while incarcerated, while some operated in law enforcement and other government offices.

Perhaps the most well-known murder case involving the Dixie Mafia is the 1967 shooting of Sheriff Buford Pusser and his wife, Pauline, in Tennessee. Pusser survived the shooting, but his wife, Pauline, died. Their story and Pusser’s fight against the Dixie Mafia became the subject of the 1970 movie “Walking Tall.” A 2004 remake of the film starred Dewayne “The Rock” Johnson as Pusser.

Pusser died in a car accident in 1974 at the age of 36. Some believe the Dixie Mafia tampered with his car to cause the accident.

By 1987 it appeared the Dixie Mafia had faded out and broken up. However, in September of that year, the group assassinated Judge Vincent Sherry and his wife. The Dixie Mafia kingpin at Louisiana State Penitentiary, Kirksey McCord Nix, Jr., ordered the hits and was ultimately sentenced to life in prison for the killings. Nix was also a suspect in the murder attempt of Sheriff Pusser and the murder of Pauline Pusser. In 1972, he was convicted of killing New Orleans grocery executive Frank Corso on April 11, 1971.

After the Sherry murders, it became clear the Dixie Mafia was still active, so it is fair to say that the group could have played a hand in Norman’s murder. However, it has never been proven.

The Ladners continued their fight for justice but were unsuccessful, and their son’s case remains closed. Norman Ladner Sr. passed away in 2003 at the age of 66.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

The investigation, if you want to call it that, was a complete joke. Southern police officers are something else! I think, at the very least, Lumpkin should have initially called the death suspicious. He ascertained no foul play by simply looking at the crime scene at NIGHT. He immediately ruled it out BEFORE the autopsy. Right there, that tells me something was fishy from the get-go.

The suicide ruling is questionable on so many levels, but the main problem I have with it is how did Norman shoot HIMSELF in the TEMPLE with a RIFLE? I’m no gun expert, but that seems like it would be tough to do unless you’re Stretch Armstrong.

How did he get the laceration on top of his head if he shot himself? I agree with his father; he would have received it on the back or side of his head, definitely NOT THE TOP. And I don’t believe it was from the tree root either. Someone hit Norman on the head with a gun, and when he fell to the ground, the assailant shot him.

Why did Stafford rule suicide in Norman’s death after he told Ladner he believed it was accidental? Did someone threaten him or give him hush money to do it?

What reason did Norman have to take his own life? There were no family problems, he didn’t use or abuse alcohol or drugs, and he was a good student.

I don’t believe his death was accidental either. Norman was responsible and smart; he knew how to handle a gun and would have been careful.

Lumpkin said he initially thought Norman had climbed a tree, fell, and the gun accidentally discharged. Why in the hell would he have climbed a tree carrying a gun while hunting? For that matter, why would he climb a tree? And what animal was Norman hunting in August??

Norman was murdered, and we’ll never know by who. I’m not sure the Dixie Mafia was involved, but it does kind of point that way. There is little doubt that Lumpkin covered up the crime.

I think Norman Ladner saw something each should not have seen in the woods that day. Some people believe that Norman’s case might be related to the 1987 murder of Don Henry and Kevin Ives.