Peter Olenchuk, 48, was an Army brigadier general and commanding officer of the Army Ammunition Supply Depot in Joliet, Illinois. He was married to Ruth Olenchuk, and the couple had three daughters – Nancy, Jane, and Mary.

The Olenchuks had a seven-room summer cottage in Ogunquit, Maine where they stayed each summer. Ogunquit is a small coastal town about 12 miles south of Kennebunkport.

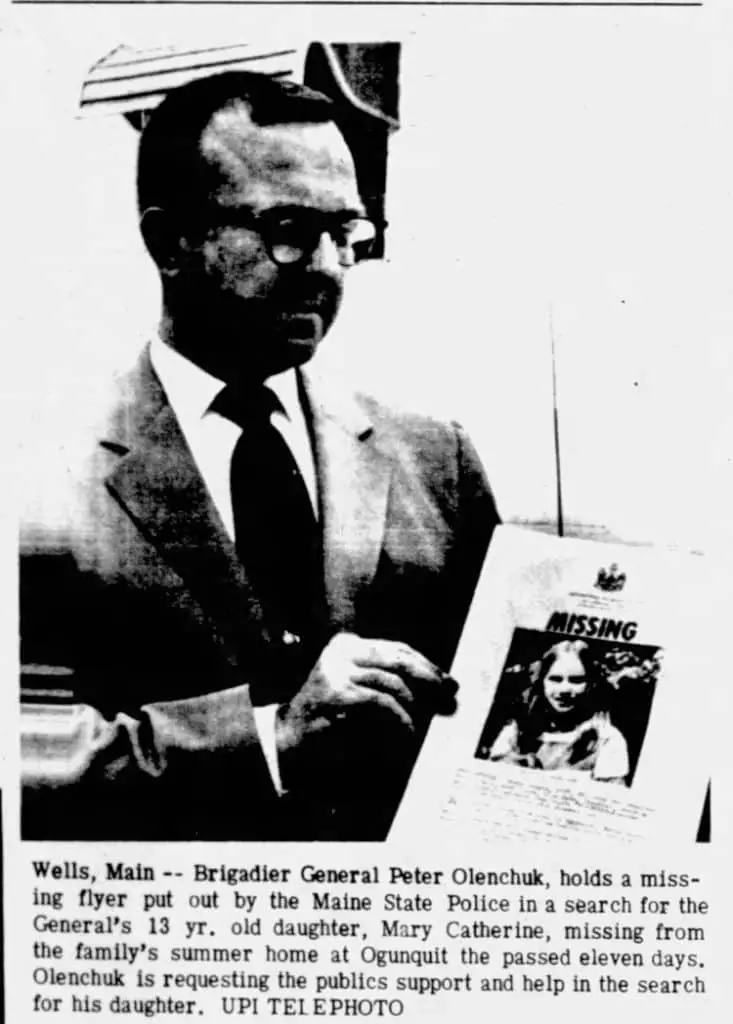

On Sunday, August 9, 1970, red-haired, blue-eyed Mary Olenchuk, 13, left the beach on a bicycle she borrowed from a friend to get a pack of gum and newspaper. She was last seen at 5 pm, talking to an unidentified man in his 30s outside the Lookout Hotel, located at 55 Israel Head Road, just 200 yards away from her home.

He was driving a faded maroon sedan with a scratched hood. A woman staying at the hotel said it appeared that Mary was giving the man directions. She also said she saw Mary enter the man’s vehicle.

When Mary failed to return home by 7 pm, her mother called the police to report her missing.

Police found Mary’s bicycle propped up against the wall of a breezeway at the Lookout Hotel, but there was no sign of the young girl.

Over the next several days, a massive air and ground search took place. Green Berets piloted Army helicopters to scout a three-mile coastal strip north of Ogunquit for abandoned vehicles near wooded areas. Volunteer firefighters combed the woods for clues to Mary’s whereabouts but found nothing.

Her parents waited for two days for a ransom call, but they never received one.

During the search, Mary’s family remained in seclusion.

Operation CHASE

General Peter Olenchuk oversaw Operation CHASE (the acronym for “Cut Holes and Sink ‘Em”). It was an ocean disposal program where the Army loaded chemical weapons on to ships and later dumped them at various locations in the ocean.

The first chemical sinking was designated CHASE 8 in 1967 and disposed of mustard agent in ton containers and M55 GB-filled rockets. In June 1968, CHASE 11 disposed of GB and VX in ton containers and rockets. CHASE 12 in August 1968 disposed of mustard agent in ton containers. The last was CHASE 10, delayed for various reasons, but finally completed in August 1970. It disposed of about 3,000 tons of nerve agent rockets encased in concrete vaults. Environmental concern over the sea dumping of chemical weapons led to a public law [Marine Protection, Research & Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (MPRSA) ] prohibiting further such missions.

GlobalSecurity.org

According to Jesse Ellison of DownEast.com, on August 8, 1970, one day before Mary’s disappearance, “a Kentucky newspaper reported a threat from a student group that said it would kidnap the families of those involved.”

At a press conference in August 20, 1970, Peter said he was chosen for the nerve gas assignment because of his training in chemical warfare and doubted his daughter’s abduction was related to his work. Police found no evidence linking the two together.

Other than a brief phone interview in 1971, Peter Olenchuk never again spoke publicly about his daughter’s murder.

A Sad Discovery

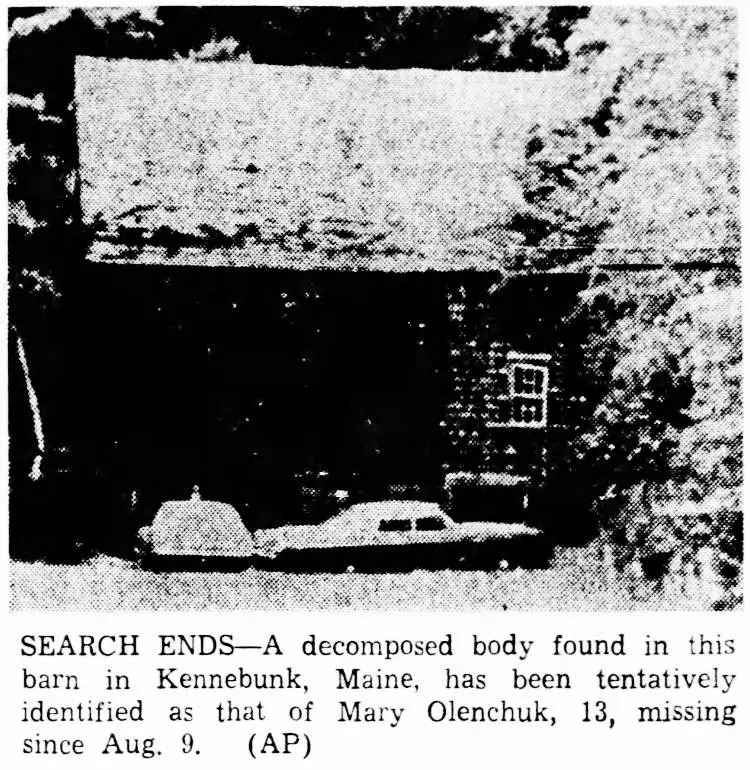

On Saturday, August 22, 1970, special policeman George LaBarge had been searching all day for Mary and was probing an area around the Parson’s farm on Brown Street near the Mauson River. LaBarge decided to explore a barn on the property.

Hidden under a pile of hay, LaBarge found the partly decomposed body of Mary Olenchuk. The barn was only a few miles from the Olenchuk’s summer cottage. It had been checked earlier during the two weeks of searching.

Police believed the killer was familiar with the barn. Several hippies had camped out on the farm in the weeks before the killing.

Authorities transported the body to a hospital in Waterville, where Dr. Irving Goodoff, a deputy chief medical examiner, performed the post mortem.

The autopsy revealed Mary was strangled to death. A piece of rope had been wrapped tightly around her neck. She had no other physical injuries on her body.

Dr. Goodoff found traces of black human hair and skin under Mary’s fingernails, which indicated a violent struggle, and Mary fought back.

Her clothes were intact, and there was no evidence of a sexual assault. With no sexual assault, police were at a loss for a motive in the killing.

Tourist Influx a Problem

Dave Swearingen of the Associated Press wrote in 1971 that “one of the biggest problems encountered is that the area’s population, swelled by the annual tourist influx, goes from the hundreds in the winter to about 100,000 in the summer.”

The temperature hit 90 degrees the weekend Mary disappeared. Thousands of vacationers hit the beach to cool off, which hampered police efforts to locate Mary.

Mary Olenchuk’s killer may have been a tourist who fled the area shortly after her murder.

Other Murders

Mary Olenchuk’s murder was similar to other killings that occurred in New Hampshire one year earlier, and police explored possible connections.

On January 29, 1969, 11-year-old Debbie Horn of Allentown, NH, stayed home sick from school after falling on the ice and had complained of pain. When her mother returned home from work at lunchtime, the backdoor was open, and Debbie was gone. Debbie’s unclothed, decomposed body was found 20 miles from home in the trunk of an old abandoned car in August 1969.

On July 4, 1969, Debbie Horn’s teacher, Luella Marie Blakeslee, 29, disappeared. Her body was found 29 years later in 1998. Robert G. Breest, her boyfriend, was later convicted in the 1971 slaying of 18-year-old Susan Randall in Concord, N.H., and has been a long-time suspect in Debbie and Luella’s murders.

On November 22, 1969, 13-year-old Michele Wilson from Massachusetts, disappeared while riding her bicycle. In March 1979, child killer Charles Pierce confessed to her murder and led police to her body.

Pierce accosted her as she rode her bicycle home from a friend’s house, dragged her into his van, and strangled her. Then he had sex with her dead body and took her to some woods, where he bit her, beat her, kicked her in the head, put a 98-pound rock on her head and covered her with leaves, according to Robert Weiner, the Essex County first assistant district attorney who prosecuted the case in 1979 and 1980.

Judith Gaines, The Boston Globe, July 9, 1999.

Although Pierce confessed to other child murders, he never mentioned killing Mary Olenchuk.

In all three cases, the young girls disappeared in broad daylight on frequently traveled roads.

Mary, Debbie, and Michele each had dogs. Police theorized that each girl went willingly with her abductor, lured by the ruse that an animal was hurt.

Aftermath

Peter Olenchuk spoke to the press around the first anniversary of his daughter’s murder but never spoke publicly again. He later retired from the Army.

Peter was named to the Lebanon Valley College Board of Trustees as an alumni trustee in 1980. He was a 1942 graduate of the college, located in Pennsylvania.

In September 1980, police announced they had linked an unidentified suspect to Mary Olenchuk’s murder through a tip. However, at that time, he had not been questioned because the police did not have enough evidence to convict him.

Mary’s father, Peter died in 2000, two years after her mother, Ruth’s death in 1998.

Mary’s oldest sister, Nancy, legally changed her name to Hilary. She died from multiple myeloma on May 11, 2014. Her other sister, Jane, is now around 69 years old.

On the 37th anniversary of Mary’s murder, police made a public appeal for information in the case.

If you have any information about Mary Olenchuk’s murder, please call Maine State Police at 1-800-228-0857.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

I think it’s possible Peter Olenchuk’s work may have had something to do with Mary’s murder. Is it just a coincidence that one day before Mary’s abduction, a student group threatened the families of Operation CHASE and the very next day, she’s gone?

Mary’s murder happened on the heels of the Kent State massacre on May 4, 1970, so tensions were running pretty high across the country.

Soon after, the government dumped a bunch of chemical weapons into the ocean off the coast of Florida, and her father was in charge of it. Police said they didn’t find a connection, but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t one.

There were many tourists in the area on the day Mary disappeared, so her murderer may have been among them and not tied to Peter’s work. What bothers me about this theory is that there was no evidence of sexual assault, which would have been a motive for the killing.

I do find it a little strange that Peter never spoke publicly about his daughter after 1971. By 1980, he had retired from the army. It does make me wonder if he knew more than he let on.

Sources

“Body of Missing Girl Found in Maine Barn. The Boston Globe. August 23, 1970.

“Copters Join Hunt for Girl.” The Boston Globe. August 13, 1970.

Cullen, John F. “Pets Seen Link in 3 Girls’ Deaths.” The Boston Globe. September 1, 1970.

Ellison, Jesse. “Closure?” DownEast.com. https://downeast.com/features/unsolved-crimes-closure. Accessed May 26, 2020.

“Girl’s Father Directed Gas Train.” The Boston Globe. August 21, 1970.

“Green Berets Join Hunt for Girl.” The Boston Globe. August 14, 1970.

Juda, Daniel P. “Murder in Maine Likened to Debbie’s.” The Boston Globe. August 24, 1970.

“Mary Catherine Olenchuk.” The News. August 26, 1970.

“Missing Girl is Sought in Maine. The Boston Globe. August 13, 1970.

“Retired General Named LVC Alumni Trustee.” Sunday News. August 17, 1980.

Stack, James. “Olenchuk Murder Unsolved.” The Boston Globe. September 7, 1980.

Swearingen, Dave. “Maine Hunt Goes on for Girl’s Killer.” The Boston Globe. August 8, 1971.

United Press International. “Search Still on for Missing Girl 13.” The Boston Globe. August 17, 1970.