Mario Amado, 29, and his girlfriend Patty Griffin arrived in Rosarito Beach, Mexico, at 1 a.m. on June 6, 1992, joined by Amado’s older brother, Joe Amado, 49, and his fiancée, Debbie Larson. The group stayed at a Mexican condo owned by Griffin. Both couples lived and worked in North Hollywood, California, and they were looking forward to fun and relaxation.

The couples partied until about 4 a.m. when Joe Amado and Larson went to bed. At 7 a.m, they awoke to Amado and Griffin fighting.

Amado told his brother that he wanted to return to California. However, by late morning, the couple seemed to be getting along. Amado appeared to be happy, as if everything was fine.

Joe Amado and Larson went for a drive along the coast in the afternoon while Amado and Griffin remained in the condo, partying.

A fight between Amado and Griffin escalated on the front porch. A condo security guard called the police at 4:30 p.m. Griffin told the responding officers that Amado was drunk and had hit her, but she refused to press charges. However, she signed a complaint against Amado for being drunk and disorderly.

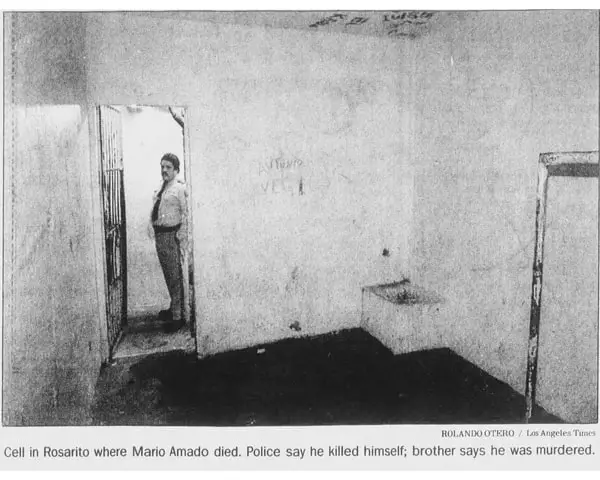

The officers arrested Amado for drunkenness and disorderly conduct but never charged him with a crime. They escorted him to the police station, placing him in Cell No. 2 with four borrachos or drunks. They later claimed they wanted Amado to sleep off the alcohol, like the others.

Meanwhile, Joe Amado and Larson returned to an empty and locked condo at 6:30 p.m. The key to the apartment customarily kept under the mat was gone. A housekeeper told them that Amado and Griffin had fought.

Larson crawled through a window to gain entry. Suddenly, four Tijuana police officers arrived and asked for Griffin by name, never mentioning Amado’s arrest.

Joe Amado and Larson told them she might be at a nearby bar. A suspicious Larson followed them and watched as they frantically searched for Griffin at the bar.

In a segment on “Unsolved Mysteries,” Larson said: “A little while later, Mario’s girlfriend comes just waltzing in the house. Like nothing was wrong. We asked her where Mario was. She said she didn’t know.”

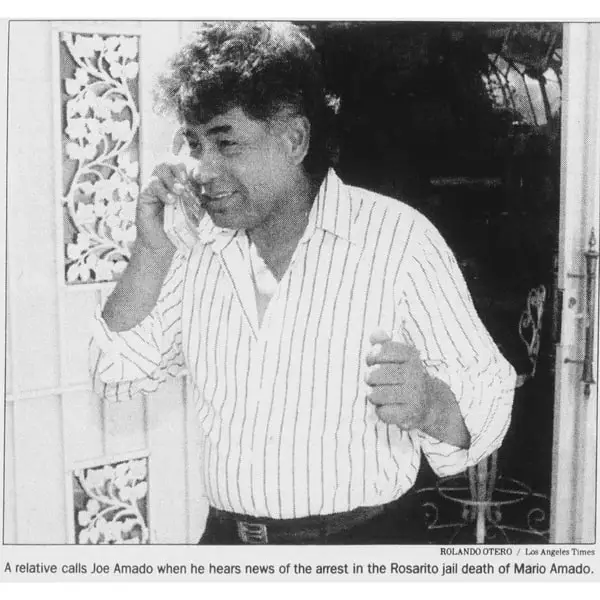

Two hours later, a few detectives arrived at the condo. Joe Amado still did not know that Amado had been arrested, so he was shocked when the detectives told him that Amado was dead.

According to the police, one of the drunken cellmates hollered out to the guards at 5:15 p.m., 45 minutes after Amado’s arrest, that Amado had hanged himself.

The detectives took Joe Amado to identify his brother’s body. One of the detectives showed him four pictures of Amado’s body and asked if that was his brother. He confirmed it and immediately noticed that his brother was shirtless. Mexican detectives claimed that Amado used his sweater to hang himself in his cell in the presence of four cellmates, who later claimed they were asleep and never heard anything.

Joe Amado asked how his brother had hung himself with the sweater. The detective told him that Amado tied one sweater arm around his neck and the other around a crossbar on the cell door and quickly sat down. The crossbar was only three to four feet from the ground. Joe Amado did not believe the official story of his brother’s death.

Joe Amado and their sister Delores Amado claimed that Mexican police purposely misidentified Amado’s body as “Vicente Amador” on Amado’s toe tag. They theorized officials wanted his body to remain unclaimed and cremated, destroying any evidence of murder.

During Amado’s jail stay, officers who were present denied any misconduct, and Mexican officials insisted he had killed himself.

After Amado’s death, Mexican authorities never contacted the U.S. Embassy and violated international agreements. Consulate officials learned of Amado’s death from newspaper reports.

Mexican police refused to release Amado’s body pending an autopsy, completed on June 8, 1992. It listed the cause of death as “a loss of oxygen to the brain,” the result of Amado hanging himself. Authorities closed the case.

Dolores Amado convinced the Mexican authorities to give her Amado’s gray pullover sweater he allegedly used to hang himself. Joe Amado later handed it over to FBI agents for testing.

Believing that jailers had killed his brother, Joe Amado contacted California Congressman Howard Berman, who did his own investigation.

Berman said on “Unsolved Mysteries, “The Mexican autopsy confirmed the report of the jailers in Tijuana that Mario Amado had hung himself with his own sweater. This is the oldest excuse for a jail murder, that the prisoner hung himself.”

Amado’s body was returned to the U.S., and his brother hired Dr. Richard Stiegler, an L.A. pathologist, to do the second autopsy.

Steigler conducted the autopsy on June 12, 1992, and discovered three cups of blood in the liver capsule, which he said was also documented by a Mexican coroner. Steigler wrote, “There is strong evidence for a blow to the upper abdomen. Such a blow and the resulting hemorrhage would likely produce shock, during which time the victim would not likely have been able to hang himself.”

Stiegler submitted his autopsy report to the Mexican federal authorities in August 1992.

A few months later, Los Angeles County Chief Medical Examiner-Coroner Lakshmanan Sathyavagiswaran concluded in a second autopsy that he “would not certify this case as a suicidal hanging.” He stated that Amado’s death appeared to have been caused by “blunt force trauma to the abdomen, and neck compression.”

Berman suspected a cover-up and wrote to Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who reopened the case.

Amado’s body was exhumed in January 1993 for a third autopsy commissioned by the Mexican government and conducted by Kings County forensic pathologist Dr. Armand Dollinger, who ultimately reclassified Amado’s death as a homicide.

Dollinger stated in his 11-page report that Amado had been drinking alcohol and was under the influence of “a significant level of cocaine,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

He further wrote that the level of cocaine Amado ingested “is not the toxicological pattern I would expect in a person experiencing a suicidal depression.”

Dollinger believed someone had strangled Amado with a ligature other than a sweater. Tests completed on the shirt at the FBI Lab, then located in Washington D.C., revealed the existence of unexplained fibers embedded in Amado’s neck, which suggested that the “instrument of strangulation” was a ligature, possibly “a rope or narrow belt.”

Joe Amado found some relief when Mexican authorities arrested Rosarito municipal police officer Jose Antonio Verduzco Flores, then 35, for Amado’s murder in May 1993. However, the elder Amado believed that more than one police officer killed his brother. Verduzco and two fellow municipal officers said he did not arrive at work that day until after Amado’s death. His arrest fueled accusations of a police cover-up.

Verduzco was later tried and convicted. However, the Los Angeles Times reported in 1996 that “a three-judge panel in Mexicali overturned his conviction, contending that Amado might have suffered fatal injuries while roller skating before his arrest or possibly committed suicide.”

Joe Amado fought hard to get justice for his baby brother. He first proved his brother did not kill himself and unintentionally spotlighted a continuing problem of abuse of foreigners in Mexican jails.

In a 1993 L.A. Times article, Josh Meyer wrote, “The U.S. State Department reported that Mexican authorities had arrested 977 Americans in 1992, and there were 67 cases of alleged mistreatment, mostly during interrogation or detention, and 13 protests lodged by U.S. Officials… At least three other Americans died under mysterious circumstances in Mexican jails between 1992 and 1993.”

Over a decade after Amado’s death, another U.S. citizen died in Mexican custody in somewhat similar circumstances.

David Echavarria Garcia, 40, was a U.S. Army veteran born and raised in Santa Paula, California. Garcia, his wife, and their seven children resided in Tijuana. The Garcias worked in San Diego but moved across the border, where it was cheaper to live.

Garcia had been honorably discharged from the army and in and out of jail for alcohol-fueled crimes. Tijuana police arrested Garcia on July 23, 2003, two days shy of his 41st birthday. Garcia called his sister Anna Cantero in Santa Paula to tell her he had been arrested for possessing a weapon and placed in the La Mesa jail. He said the weapon was a knife.

Garcia wanted Cantero to notify his wife to bring clothes and money while he waited for arraignment. The Garcias did not own a landline telephone. He often called his sister in September and October 2003 to ask if she had gotten word to his wife.

Finally, in November 2003, Lori Garcia visited her husband in jail. She had to have three forms of identification and a long wait before approval.

The last time Cantero heard from her brother was on Thanksgiving Day in 2003, when he said he was sick with the flu and a prison doctor had treated him.

Garcia never contacted Cantero after that phone call. She called the U.S. Embassy in Tijuana on March 1, 2004. Two weeks later, a consulate employee finally called to inform her that no record of her brother’s incarceration existed.

Cantero called the jail, and a jailer told her the same thing, even though she had his booking number. She filed a missing person report on March 16, 2004. Three days later, a consulate official contacted her and said they had found Garcia and would visit him to advise him of his rights.

On March 24, 2004, a consulate supervisor phoned Cantero, telling her that Garcia had been dead since Dec. 13, 2003. Mexican records showed that he had no next of kin even though his wife had visited him in jail and Contero had called the prison looking for him.

Shortly after, Cantero and their sister Irene Nava viewed pictures of Garcia’s body at the morgue. Officials claimed he had died of liver cirrhosis, but they could see signs of abuse on his body. Garcia had blood on his nose, swollen lips, and bruises on his right arm. None of the photos showed the left side of Garcia’s body, where he had identifiable tattoos.

The sisters learned their brother died one day after being hospitalized.

Like in Amado’s case, Mexican officials violated international laws when they failed to report the incarceration of a U.S. citizen. U.S. officials filed a protest with Mexican authorities over the matter.

When consulate employees attempted to locate Garcia in their regular prison checks, they learned that jailers booked him under a different name. As mentioned earlier, Amado’s family accused Mexican authorities of purposely misidentifying Amado’s body.

Consulate officials visited the jail in September 2003 but never saw Garcia. His body was exhumed in July 2004 and cremated the same day, per his family’s request. Even though they believed jailers had killed Garcia, they did not have the money or resources to pursue the matter further. They buried his remains next to his mother’s at a California cemetery.

There’s little doubt that abuse against tourists in foreign jails still exists today in Mexico and worldwide. I wrote about British tourist Lee Bradley Brown‘s torture and death in a Dubai jail.

Besides Verduzco’s arrest, no one else has been charged with murdering Mario Amado and likely never will.

According to her three Facebook pages, Patty Griffin currently lives in Colorado.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

I have never been to Mexico. I have never had any desire to, even though I know many people who visited and loved it. But the true-crime blogger in me says, “NOPE.” I’ve read too many horror stories out of Mexico, like Americans getting their drinks laced with drugs, for example. No, thank you.

This one is obvious. The jailers killed Amado. I believe one or all of the drunk cellmates also witnessed it but were probably too scared to say anything.

The jailers weren’t too bright if they actually thought his family would buy that he hung himself with a freaking sweater 3-4 feet off the ground. What reason would he have had to take his life in jail? He had only been there for 45 minutes when he died.

Patty Griffin, well, she’s a real piece of work, isn’t she? I don’t believe she had anything to do with his murder because she wasn’t there, but she was not a nice person. She didn’t have to kick Amado out of the condo when Joe and Debbie were gone; she could have made all of them leave when the couple returned. Even though she did not press charges, she signed a complaint, something else she did not have to do.

Where was Griffin between 4:30 and 6:30 p.m. when the police came looking for her? Did she know any of the jailers? She owned the condo, so maybe she had befriended some locals.

That may be a stretch to say she had a jailer friend kill Amado, but I want to know why they killed him. Police arrested him at 4:30 p.m., and at 5:15, one of his cellmates hollered that he had hung himself.

Amado doesn’t strike me as a man who would have been an unruly prisoner. Maybe the torture went too far, and they had to kill him to cover it up. That is probably the best scenario. We know they punched him in the upper abdomen because of the 3 cups of blood found in the liver capsule.

In both the Amado and Garcia cases, the police purposely misidentified them. I wonder how many U.S. citizens were killed there, and their loved ones never knew because of misidentification.

I find it interesting that Griffin never did any interviews on Amado’s death that I could find. She was not on “Unsolved Mysteries” either. That speaks volumes to me; she didn’t give two shits about Amado. In 2017, she married a man who bears a striking resemblance to her long-gone boyfriend.