Maoma Little Ridings was born in Abbeville, Georgia, on April 6, 1910, to Omar and Mae Little.

She grew up in Warm Springs, Georgia, and was a descendant of the prominent Bulloch family, who founded Warm Springs.

Maoma attended school in Georgia and was a student at Georgia State Normal College in Athens. She married Lawrence Ridings of the U.S. Army, but the two later divorced.

From 1927 to 1931, she worked as a nurse in Warm Springs, at which time she met then-Governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“He used to call her ‘husky’ because she was so strong,” her grandmother, Annie Bulloch told The Franklin Evening Star in 1943. “And he would tell her she was one of his favorite nurses.”

Maoma later gained employment as an auditor at the Federal Housing Administration in Washington, D.C.

In January 1943, she joined the Woman’s Army Corps (WAC) and arrived at Camp Atterbury in Indiana shortly after.

The Murder

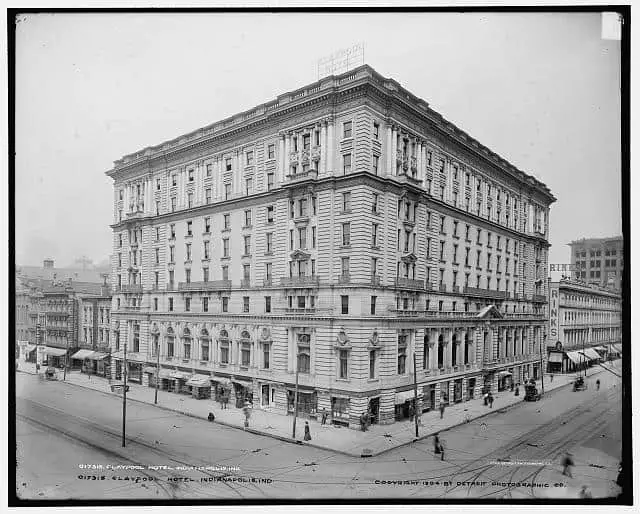

On August 28, 1943, Maoma Ridings checked in to room 729 at the Claypool Hotel in downtown Indianapolis, which is now defunct. She was a frequent weekend guest at the hotel that summer, often coming alone or sometimes with another woman from Camp Atterbury, Ruth Hoover.

Maoma and Ruth often attended weekend parties at the Hotel Severin but stopped going after the hotel demanded Maoma pay for a broken bed. The two then attended parties at the Claypool.

Later in the night on August 28, the Claypool hotel switchboard received a call from a woman who reported hearing another woman scream in a hotel room occupied by a Camp Atterbury soldier.

A hotel employee went to the room, which was on the same floor as Maoma’s room. However, the room was empty, and the soldier had checked out.

At 8 pm, hotel housekeeper Lillian McNemar (some reports say McNamara) was doing her nightly room inspection when she knocked on Maoma’s room. When no one answered, Lillian, entered and found Maoma

Ridings dead in a pool of blood.

The Investigation

Detective Fae Davis and Lieutenant Noel Jones of the Indianapolis Police Department arrived at the crime scene.

Maoma was wearing a regulation WAC shirt, skirt, and stockings, although the clothing was disarranged. A crumpled, blood-stained undergarment lay near the body.

Her face, throat, and wrists had been slashed. Detectives found a broken whiskey bottle in the room. An autopsy later revealed a blow to the head had killed her.

Detectives theorized the killer had struck Maoma with the whole fifth-sized whiskey bottle and then used the shattered pieces to inflict the gashes.

Maoma had purchased the whiskey bottle and six bottles of Coca-Cola that evening.

Witnesses said they heard the soldier and a woman arguing in his room. The woman asked the telephone operator to send a hotel detective to her room (The Atlanta Constitution, August 30, 1943).

The Woman in Black

Davis questioned two bellboys named Alfred Bayne and Robert Wolfington, who said they had taken refreshments to Maoma Ridings’ room. Bayne recalled seeing a “black-haired woman” in the room during the evening.

Bayne told the detectives, “The woman (in black) kept silent while I was in the room, but she appeared to be in good humor. Cpl. Ridings also was in good spirits, and she tipped me in paying for the soft drink.”

He described the “woman in black” as between 38 and 40 years old, attractive with black hair, wearing a black dress and a black hat with a black veil.

Detectives did not rule out the possibility of a man dressed in women’s clothing. Baynes said, “She might have been a man, but she looked pretty feminine to me.”

Police questioned Ruth Hoover, who sometimes accompanied Maoma to Indianapolis, as possibly being the “woman in black” or having valuable information that might have been helpful to detectives. Ruth, 37, had dark hair, and often wore a black dress while in Indy. She claimed she was visiting relatives in her hometown, Water Valley, Mississippi, at the time of the murder and then traveled to her residence in Jackson, MS, 142 miles south of Water Valley.

Ruth was in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) but left the Army on August 4, 1943, shortly before the WAAC’s conversion to WAC. Her job changed from a clerk in the Headquarters Company to a fireman.

She had intended to show investigators a letter written by Maoma Ridings two days before her murder. Maoma wrote in the letter that she had testified at a court-martial hearing against a Camp Atterbury soldier. However, the soldier in question was in the army base’s guardhouse on the night of the murder.

Ruth told authorities about their party days at Hotel Severin. These weekend parties included enlisted men and officers, and the party-goers frequently drank alcohol the entire weekend. There was a middle-aged civilian man in the group who regularly attended parties at the Severin. He was well-liked by the party group but did not participate in the Claypool parties. Ruth said they never saw him again.

Ruth found it strange that Maoma had ordered six Coca-Cola bottles because Maoma always drank her whiskey straight with a chaser. She did not believe a woman had been in the room, saying, “Ridings didn’t like women – she liked men.”

The Investigation Continued

Army authorities originally wanted to join in the investigation. A couple of days later, they turned it over to Indianapolis after determining the crime was a case for city officials.

Lawrence Ridings, Maoma’s ex-husband, was overseas at the time of her murder and ruled out as a suspect.

A few days after the murder, police revealed that an unidentified man placed a call to Maoma’s hotel room after discovering her body.

A detective answered the call. He said the man had a “smooth-sounding voice,” and asked for “Miss Ridings.” When the detective said she was not in her room, the caller replied, “Thanks very much.” The man hung up the phone when the detective asked his name.

On August 30, 1943, Richard Fear, an 18-year-old soft drink concessioner in a New Castle, IN war plant surrendered to police and confessed to Maoma’s murder, saying, “I cut her throat, but I didn’t’ think she was dead.”

The police said Fear’s story did not match the facts. Judge John Niblack asked the youth, “Why did you say you did?” He replied that his friends had teased him about being in Indianapolis, so he made up the story.

In early September 1943, Chief Prosecutor Saul Rabb said that Maoma L. Ridings’ killer had attempted to hide her body in a closet in her hotel room. He based his theory on a blood clot found on the closet floor by a deputy prosecutor named Mary Rader.

Authorities questioned more hotel staff and an Army deserter named Maurice Philpott, who was in Indianapolis on the night of the murder. They ruled him out as a suspect, although it is unclear why.

Rabb concluded that Maoma knew her killer. The housekeeper, Lillian, said the transom was open when she arrived at Maoma’s room. If Maoma had not known her killer, surely someone on the seventh floor would have heard something, he reasoned.

Victim Placed Phone Calls to Three Men

Chief of Detectives Jesse McMurty checked registration and service records of two downtown Indy hotels – the Claypool and the Hotel Severin.

Maoma Ridings had placed long-distance phone calls to three different men on previous visits to Indianapolis. She made one call to Waverly, Tennessee, and the others to Georgia and Mississippi. Police never released the men’s names but did say one was a member of a wealthy Northside family, another was a chief engineer of an Indy war plant, and the third man was a salesman. The engineer and salesman were both married.

The wealthy man and the salesman received calls from Maoma on April 23, 1943. According to the Indianapolis Star, it was “The day that marked the beginning of a three-day party in room 902 of the Hotel Severin. After the party, the room was a shambles – ‘the bed was broken, bottles were scattered around the room, and everything in the room was topsy-turvy,’ an employee of the hotel said.”

A Possible Suspect Briefly Emerges

In October 1944, police revealed they might have found the “woman in black.”

Her name was Wiona Kidd, a 23-year-old with black hair. She married a convict named William Luallen, but the two divorced. Luallen told Indianapolis authorities that his ex-wife had killed Maoma Ridings with a broken whiskey bottle.

Luallen was a career thief. Winoa had assisted him in over 150 burglaries. The Indianapolis Star reported, “He and his former wife renewed in Indianapolis an acquaintance of several years previously with Maoma Ridings.”

Indianapolis detectives traveled to Jefferson County, Tennessee, to bring her back to Indiana for questioning. When questioned, Wiona Kidd admitted to knowing Maoma but denied killing her, saying her ex-husband was a liar.

Luallen then said he had killed Maoma Ridings, not Wiona, but recanted his confession before giving a written statement.

A short while later, he gave a second oral confession that he had killed Maoma Ridings. He told investigators that he had buried a bundle of evidence, including fragments of a whiskey bottle and a WAC skirt, near the White River in northern Indianapolis.

Law enforcement officials searched the area but never found the bundle.

Investigators said if Luallen repudiated his confession one more time, “it would have to be in court.”

A few months later, in early 1945, William Luallen appeared in front of Judge William D. Bain and asked to plead guilty to a second-degree murder charge. However, Judge Bain refused to accept his plea.

The judge said the grand jury had not indicted Luallen and that he had received information the prosecutor’s office had obtained “confessions” from two other suspects in the case (The Tribune, January 2, 1945). Officials sent Luallen back to prison to serve out the remainder of his sentence for the burglaries.

It is unclear who the two suspects were Judge Bain had mentioned.

Another Suspect and Similar Murder

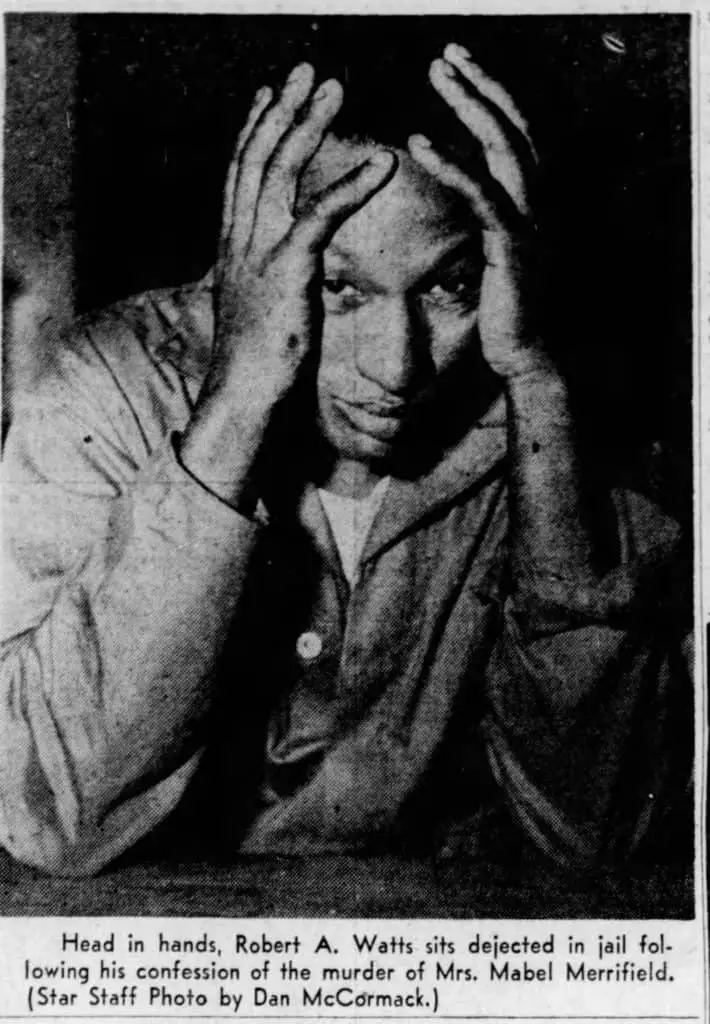

For a short while, police suspected Robert Austin Watts of Maoma Ridings’ murder. He confessed to killing an Indianapolis woman named Mabel Merrifield, 68, in October 1947. Watts also admitted to being an intruder in the home of another woman.

Watts, 25, was convicted in August 1946 of being a Peeping Tom and had a rape charge a few months later.

Mabel Merrifield was brutally attacked in her home at 2583 Churchman Avenue in late October 1947. Mable’s husband found her body around 4:15 pm. She had been stabbed in the lower left side of her neck. A long, fine black hair was found clutched in Mable’s hand.

A neighbor saw a black-haired woman, about 45 years old, hurriedly leaving Mabel’s home at 12:45 pm on the day of her murder.

Police found blood-smudged fingerprints on a telephone book in the Merrifield home but said they could not determine if a man or woman left them.

On November 12, 1947, Mary Lois Burney was shot to death in her home, the result of a failed rape attempt.

Investigators questioned Robert Watts in other unsolved murders, including the killings of Maoma L. Ridings and Mabel Merrifield.

Following his arrest, Robert A. Watts confessed to the Merrifield and Burney murders, but recanted later, saying authorities forced the confessions.

Watts ultimately died in the electric chair in January 1951 for the Merrifield and Burney murders.

The mystery woman’s identity remains unknown, and police made no further attempt to locate her once Watts confessed.

Authorities failed to link him to Maoma Ridings’ murder.

Detectives looked at a couple of other suspects in the Ridings killing, but no evidence linked them to the crime.

The Dresser Drawer Murder

Dorothy Poore was 18 years old and from Clinton, Indiana. She arrived in Indianapolis on Thursday, July 15, 1954, and took a civil service examination for a typist’s job. She was to return to Clinton on Saturday, July 17.

On July 18, 1954, a hotel maid found Dorothy’s partially clothed and partially decomposed body jammed in a dresser drawer in room 665 at the Claypool Hotel.

The drawer was about 48 inches by 24 inches and approximately 10 inches deep.

Dorothy was clad only in a bra, underwear, and slip. Police found her blue jeans, slippers, and a shopping bag shoved inside the room’s air vent.

By the name of Jack O’Shea, a man had rented room 665 on Thursday, July 15, and paid for the room through the following day. O’Shea gave a false New York City address during registration.

The man also gave a wrong license plate number, which was registered to a car owned by an elderly couple staying at the Claypool.

Deputy Coroner William J. Pierce could not determine the cause of death due to decomposition but said suffocation was possible. There were no signs of violence on the body. Pierce said Dorothy had been dead for at least 36 hours when her body was discovered. That placed the time of death sometime on Friday, July 16, 1954.

A week later, authorities arrested 25-year-old Victor Hale Lively near St. Louis, Missouri.

Fingerprints and handwriting samples led police to Lively, who had stayed at the Claypool a week before the slaying. He confessed to strangling her when she rejected his sexual advances.

Lively was later convicted and sentenced to life in prison for Dorothy’s murder and paroled on July 25, 1980. He passed away less than a year later.

Indianapolis authorities stated there was no connection between the murders of Maoma Ridings and Dorothy Poore.

Aftermath

No one has ever been charged in Maoma Ridings’ murder.

On June 23, 1967, a fire broke out in a fourth-floor utility closet at the Claypool Hotel, and the hotel permanently closed its doors after that. The building was demolished two years later. Today, Embassy Suites by Hilton occupies its space.

Camp Atterbury has gone through many changes since Maoma Ridings’ time there. It is now called Atterbury-Muscatatuck.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

I chose to write on Maoma Ridings’ murder instead of Dorothy Poore’s because it did not get the media coverage that Dorothy’s murder received.

I think Maoma was killed by someone she knew because her death was overkill. As far as I can tell, she was not raped. So, I think her killing was personal. Maybe it was the soldier staying at the hotel heard arguing with a woman. I could not find anything on the soldier’s identity.

I did see one report mention that robbery might have been a motive. Detectives did not find a lot of money in Maoma’s room.

We also have the mysterious “woman in black.” If the bellboys were speaking the truth, and I believe they were, then I would be inclined to point the finger at her. It seems to me that Maoma knew her.

Maybe she was the wife or girlfriend of one of the men from the hotel parties.

The “woman in black” was dressed like a woman in mourning. I wonder if there was a reason for her to dress this way. Had she recently lost her husband? Or did she do it to disguise herself?

How many people knew Maoma was staying at the Claypool that particular weekend? Did Ruth Hoover know? She often went with Maoma to Indy and she fit the age and description of the “woman in black.” Police said she was in Mississippi at the time of Maoma’s killing, but I have to wonder how they verified this information. Did they take her for her word? If that were the case, she might have lied.

There is nothing more on Ruth Hoover after September 1943.

Sources

“Denies Killing WAC Corporal.” Vidette-Messenger of Porter County. October 25, 1944. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/333133946

“Detectives to Question Him Again.” The Indianapolis Star. November 21, 1947. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/104951858

“Divorcee is Due Today for WAC Murder Quiz.” The Indianapolis Star. October 26, 1944. Accessed July 30, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/104904874

“Doubt Story of New Castle Boy.” Muncie Evening Press. August 31, 1943. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/249327994

“Girl Found Jammed Into Indianapolis Hotel Room Drawer; Man is Hunted.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN). July 19, 1954. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/253284806

“Indianapolis Officers Baffled at Slaying of Georgia WAC.” Atlanta Constitution. August 30, 1943. Accessed August 1, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/398216521

“Judge Refuses Guilty Plea in WAC Slaying.” The Tribune (Seymour, IN). January 2, 1945. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/160477159

“Man Sought in Atterbury WAC Slaying.” Franklin Evening Star (Franklin, IN). August 31, 1943. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/95965644

Mitchell, Dawn. “True Crime: The ‘dresser drawer murder’ at the Claypool Hotel.” The Indianapolis Star. July 15, 2018. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/457110757

Penner, Diana. “Mystery Still Surrounds 1943 Slaying of WAC.” The Indianapolis Star. October 6, 2013. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/106644582

“Repudiates Confession in Murder.” The Times (Muncie, IN). November 1, 1944. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/310524844

“Seek Slain WAC’S Skirt.” The Times (Muncie, IN). November 2, 1944. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/310525960

“Slayer of WAC Tried to Hide Body in Closet.” The Times (Munster, IN). September 7, 1943. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/307676341

“To Quiz Indianapolis Men in WAC Slaying.” Star Press (Muncie, IN). September 10, 1943. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/249590085

“WAC’S Slashed body is Found in Room of Indianapolis Hotel.” Star Press (Muncie, IN). August 29, 1943. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/249589699