William “Hokey” Hokanson, Sr., 44, was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts to Fritz and Sallie Hokanson. He had lived in Carver and Acushnet before relocating to Fairhaven in 1978.

Hokey grew up in a family of fishermen, but tragedy struck when he was a child. In mid-February 1952, a violent Nor’easter took his father’s life. Fritz Hokanson, 43, was aboard the 79-foot schooner Paolina with six others, including Hokey’s uncle, when Fritz radioed home to his mother saying he would be waiting out the storm. The Coast Guard scoured 14,000 square miles for the Paolina but only found the ship’s orange dory 150 miles southeast of the Nantucket Lightship. The storm sunk the rest of the vessel and split two large tankers in two, killing 14 people. Fritz and his crew were lost at sea.

There were a series of Nor’easters that year, with this one being the first. The second occurred 11 days after the first one and was considered “one of the worst northeast snowstorms to hit Southern New England in 50 years,” The Berkshire Eagle reported in 1952.

Many years later, Hokey and his two brothers, Richard and Robert, were fishing when caught in a violent storm. Richard and Robert never returned to the sea, but Hokey’s love for the ocean and fishing lured him back to the watery abyss.

Hokey married twice, but both marriages ended in divorce. He had a daughter, Cheryl, and a son, William “Billy” Hokanson, Jr., with ex-wife Ellen Oullette.

Billy, 19, graduated from New Bedford Vocational High School in 1989. During high school, he played varsity hockey and focused on marine biology because he wanted to one day earn a living fishing. He purchased his first boat, the Hokey II, a 40-foot craft used mainly as a gearboat in the family fishing business.

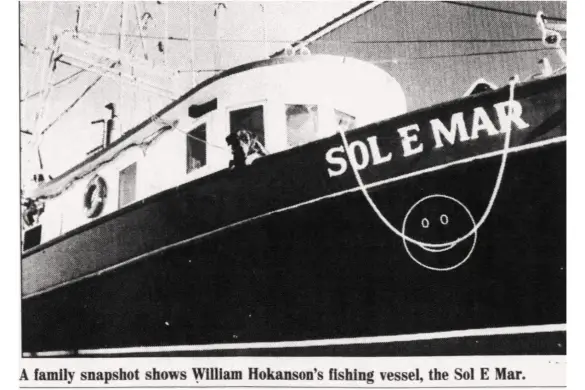

Hokey owned the Sol E Mar, a 58-foot fishing vessel (some reports say 50 and 70). The men moored both boats at Boston’s Kelly’s Landing during the spring and summer and in Boston Harbor for winter fishing.

The father and son often went on three- or four-day fishing trips aboard the Sol E Mar. They would moor the boat at night and sleep on shore. However, on one trip, the pair never returned.

Lost at Sea

On Thursday, March 22, 1990, Hokey, Billy, and the family dog boarded the Sol E Mar and departed Kelly’s Landing, headed for Cape Cod, hoping to catch some large flounder. They were scheduled to return the following Wednesday.

On March 25, Billy called his girlfriend aboard the boat via a cellular telephone. He and his father were near Nomans Land Island, an uninhabited island 10 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard that remains closed to the public. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, there are “potential safety risks associated with unexploded ordnance and the value of this island as a relatively natural island habitat,” so the island remains “closed to all public uses.”

Billy told his girlfriend they would return to Fairhaven by Wednesday, March 28. He and his father also notified another fishing vessel about their return on Wednesday.

Later that night, at 9:18 p.m., Billy placed a frantic four-second call using VHF radio channel 16, the “mariner’s 911.” The Coast Guard picked the call up at the Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and Wood Holes stations.

“This is vessel Sol E Mar. This is a mayday. We’re sinking. We need help now!”

But it was a weak signal and hard to understand on first listening. (Fraser 2000).

According to the Messenger-Inquirer, Billy’s “plea rose into a scream. The transmission was abruptly cut. Then, there was only crackling static.”

Billy did not have time to give his location before the call was disrupted, and the men had yet to be reported missing. However, it was another call shortly after, which prevented a search and rescue from happening.

About a minute after Billy made the S.O.S. call, another distress call came in at Wood Holes Station.

“S.O.S., I’m sinking,” a male voice said, followed by laughter. The employee who took the call determined and reported both calls as hoaxes. The Coast Guard never identified the second caller. Because of that bogus call, the Coast Guard did not dispatch rescue planes or boats to search for the father and son.

Other fishermen in the area did not hear Billy’s distress call.

“Manny Santos of the fishing boat Min Flicker could not raise Sol E Mar on channels 5 or 10 after 8 p.m. but dismissed the “unusual” lack of response as due to weather problems. Santos’ boat was 2.5 miles from the Sol E Mar. He and other fishermen on nearby boats did not hear its Channel 16 distress call.” (McNiff 1990)

What caused the Sol E Mar to sink is unknown. The weather forecast that day called for light snow, and the temperature was around 40 degrees when Billy placed the radio call. So, it is possible the father and son had mechanical problems with the boat.

The Search Finally Begins

When Ellen had not heard from her son or ex-husband by Friday, March 30, 1990, she called the Coast Guard, who launched an extensive air-and-sea search at 5:30 a.m. But the chances of finding them alive a week later were slim.

The Coast Guard scoured a 10,000-square-mile area from Montauk, NY, to 20 miles east of Nantucket. However, heavy winds and rain hindered the search, and they suspended it on April 1.

“We felt that we have exhausted all the probabilities that the men are still alive,” Chief Petty Officer Jack Mason said that night.

Hokey and Billy were presumed dead and lost at sea.

After Ellen reported the men missing, Coast Guard personnel played Billy’s recorded distress call so the family could identify his voice.

Hokanson’s brother-in-law, Manuel Aguiar, said that the first S.O.S. call was clearly from Billy and the second was a different voice. (Rogers 1990)

A Brief Ray of Hope

A fisherman dredged up human remains out of the Atlantic Ocean in 1996 in the area of the Sol E Mar sinking. They were sent to a Rhode Island medical examiner. The Hokanson family sent dental records to compare, but they were inconclusive.

The family submitted their DNA 10 years ago to compare with the samples provided by the Rhode Island medical examiner. In 2015, the office had uploaded information on 25 to 30 unidentified human remains in storage.

The cross-referencing does little more than rule out bodies or remains, but the data remains in the system, said the late Todd Matthews, founder of The Doe Network and the NamUs director of communications. (Fraser 2015)

Ellen had never considered her son and ex-husband “missing,” only lost at sea. Both men have been entered into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs.

Hoax Calls

We know this country has its share of morons. For God knows what reasons, some of these morons think it is hilarious to call in a bogus mayday call to the Coast Guard, as seen in the Sol E Mar case. The problem is that the Coast Guard has taken several of these calls seriously, conducting extensive searches for boats and people that never existed. It’s a considerable cost wasted.

A man was sentenced to a year in prison in 1986 after broadcasting a bogus distress signal that triggered an enormous sea-and-air search for a sinking yacht with ten people aboard.

District One, headquartered in Boston, handles emergency calls, searches, and rescues from Canada to New Jersey. In 1989, District One received 16 recorded hoaxes, and 205 in 1990, with 11 calls by late March and eight that resulted in massive searches. That year, the “Coast Guard spent $560,000 and logged 782 hours responding to those calls.” (Howley 1991)

Demand for Better Laws and Changes

The Sol E Mar incident was the first known deaths at sea linked to a hoax distress call, according to Coast Guard officers in 1990. (Fraser 2000)

The horror of what happened to the Hokanson men made national headlines and prompted legislators in Massachusetts to change the laws on maritime emergency calls.

A new federal law titled The Studds Act, named for Rep. Gerry E. Studds (D-Mass.), took effect on November 16, 1991, and included fines of up to $250,000, up to 10 years in prison, a $5,000 civil fine, and reimbursement to the Coast Guard for costs for search operations. The old law carried a maximum fine of $10,000 and imprisonment for up to a year.

The first man to receive a jail term was Edward Chipelo, 23, after he made a fake mayday call in Febuary 1993. (Rakowsky 1994)

“I’m abandoning ship! I’m abandoning ship! I’m taking water! I’m losing my boat! I’m going over! I’m losing my crew all over!”

The Coast Guard dispatcher kept the caller on the radio while a helicopter and two cutters set out to search for the sinking boat. The longer Chipelo spoke with the dispatcher, the more it became clear his call was a hoax. The dispatcher noticed Chipelo’s words were slurring, and he became incoherent. The dispatcher could also hear the mike keying off and on. (Chamberlain 1993)

Chipelo pleaded guilty in November 1993 to transmitting a false distress signal. A few months later, U.S. District Judge Robert E. Keeton sentenced him to three months in prison, the time he had already served in jail while awaiting trial. Judge Keeton also ordered him to pay $2,534 in restitution for Coast Guard expenses and to undergo three months of inpatient substance abuse treatment and follow-up testing. (Rakowsky)

By 2000, a lot had changed in how the Coast Guard handled distress calls, but there were still problems, and Capt. Russell Webster, Commander at Group Wood Holes, remained skeptical.

At the heart of his concern is an antiquated emergency radio system, which has 65 known dead spots, including the one south of Nomans where the Hokansons perished. The old system relies on line-of-sight technology, feeding signals from eight antennas on high points along the shore. (Fraser)

That old system was Rescue 21, established in the 1970s and remains in use.

In 2000, “An updated $240 million to $300 million radio system” (Fraser) was in development with a three to six-year deployment.

Today, Rescue 21 is a state-of-the-art advanced communications system more capable and better at locating mariners in distress and saving lives and property at sea and on navigable rivers.

Rescue 21 helps identify the location of callers in distress via towers that generate lines of bearing to the source of VHF radio transmissions, thereby significantly reducing search time. It extends coverage to a minimum of 20 nautical miles from the coastline; improves information sharing and coordination with the Department of Homeland Security and other federal, state and local first responders; and can also help watchstanders recognize potential hoax calls by identifying discrepancies between callers’ reported and actual locations, thus conserving and reducing risk to valuable response resources.

The United States Coast Guard

Hoax calls remain a problem today. However, voice forensics helps identify the voices behind scam calls.

In the event of a hoax call, the towers of Rescue 21, a communications management system for the Coast Guard, triangulate a geographical area. Coast Guard Investigative Service special agents will interview local mariners and seek information from local law enforcement in that area, seeking any information that may be useful in identifying the caller. The Coast Guard can even have the recorded call played by the local media to see if anyone recognizes the voice. “It is basically good old detective work – only we are trying to identify a logical suspect based on a voice,” Marty Martinez said.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security

Recent

Capt. Webster became a maritime author, publishing several books, including “The Sol e Mar Tragedy” that he co-wrote with Elizabeth Webster. It’s available on his website and Amazon.

Brief Thoughts

It is interesting that, in hindsight, some people never considered the male caller who called in the bogus S.O.S. was aboard the Sol E Mar during the hoax call and could have caused harm to the father and son. The still-unidentified caller placed the call only one minute (some reports say 30 seconds and two minutes) after William’s frantic call and mimicked what William had said. I feel like there is something more here, but who knows?

If anyone hears a hoax call or has information that might lead to the perpetrator of a hoax, please call the nearest U.S. Coast Guard unit or contact the Federal Communications Commission.

Sources

Aucoin, Don. “Coast Guard Beings Search for Missing Father and Son.” The Boston Globe, April 1, 1990.

Chamberlain, Tony. “New Penalties for Hoaxes.” The Boston Globe, December 5, 1993.

Fraser, Doug. “Lost in the Wave.” Cape Cod Times, March 26, 2000.

Fraser, Doug. “DNA May Hold Key to Identify Those ‘Lost at Sea.'” Cape Cod Times, January 22, 2015.

Hokanson, William A. Obituary. Lost Fisherman From the Port of New Bedford, website. https://www.lostfishermen.com/person/273/William-Hokanson%20Sr. (Retrieved February 26, 2024)

Howley, Kathleen. “Crackdown Appears to Cut SOS Hoaxes.” The Boston Globe, June 16, 1991.

McNiff Jr., Tom. “Coast Guard Attempt to Rescue Pair Defended.” The Boston Globe, July 24, 1990.

O’Brien, Ellen. “Search for Fishermen is Suspended.” The Boston Globe, April 2, 1990.

Rakowsky, Judy, “New Bedford Man is First to Get Jail Time For Fals Mayday Call.” The Boston Globe, March 12, 1994.

Rogers, Tony. “Hoax SOS Call Kept Real Emergency From Being Taken Seriously.” Messenger-Inquirer (Owensboro, Kentucky), April 5, 1990.

“Smashed Lifeboat Found, Hope for 7 Seamen Dims.” The Boston Sunday Globe, February 17, 1952.