At only 18 years old, Jennifer Lynn Pentilla had already been through and done more than some experience in a lifetime.

Born on April 4, 1973, to Nick and Lynn Pentilla, Jennifer was a bright child, happy, and a “go-getter,” according to Lynn. She was definitely an outdoors girl who loved camping and hiking. She was close with her parents and loved to help decorate the home during the changing seasons and holidays.

Jennifer attended Great Falls High School in Montana and traveled solo to West Africa’s Ivory Coast during her junior year for humanitarian work.

During the first semester of her senior year, Jennifer’s father was diagnosed with Leukemia and died at 44 on October 9, 1990. Her mother later married Jim Harris.

Despite suffering such a huge loss, Jennifer graduated in the spring of 1991. That summer, she went to Mexico to do more humanitarian work, became committed to helping others, and made it her life’s mission.

Bold Decision Turns Into Fatal Mistake

Jennifer returned to Montana for a couple of months but planned to return to the country to do more missionary work. She flew to San Diego in late September 1991 with her Fuji mountain bike, camping equipment, two Bibles, a journal, $450, and other belongings.

Like many teenagers, Jennifer was fearless, maybe even a bit naive, not understanding the dangers out there. But one cannot say she was not brave. She planned to bicycle to Mexico and join fellow aid workers as part of a humanitarian project for children.

In 1991, people did not use cell phones like today, so Jennifer did not own one. She relied on pay phones to call her mother collect, dialing “0” for the operator and having the call charged to Lynn’s landline phone bill. Dialing 1-800-COLLECT was not around until 1993.

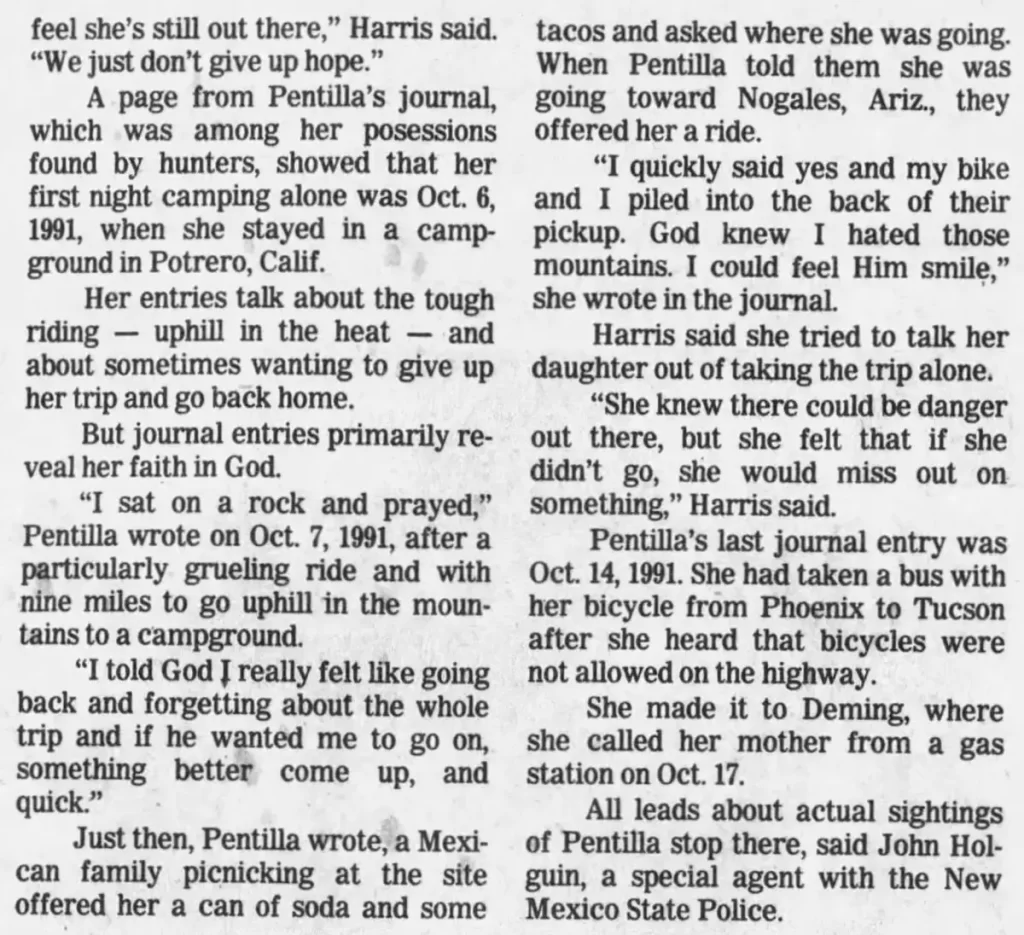

Between October 1 and October 13, Jennifer called Lynn collect eight times. During that period, she rode her bike along Interstate 10 through Southern California, Arizona, and into New Mexico, stopping in small towns and camping. She endured two flat bicycle tires, one in California and the other in Lordsburg, New Mexico, where a trucker picked her up and drove her to Deming. A local man repaired the tire.

On Wednesday, October 16, 1991, Jennifer attended a midweek church service at First Baptist Church on Pine Street in Deming. The church pastor and his wife offered Jennifer a place to sleep on their nearby property.

Across the street from the church was a Shell gas station (it is no longer there), and Jennifer decided to call her mother from the pay phone on October 17 before continuing on her journey.

Jennifer spoke with Lynn for 14 minutes, stating that someone told her riding her bicycle into Mexico was dangerous for a lone female. Instead, she decided to ride her bike to Las Cruces, then hop on a bus or hitchhike to Moorhead, Minnesota, where her friend attended Concordia College. Jennifer told her mother she would call her the next day. That was the last time Lynn spoke to her daughter.

Disappearance of Jennifer Lynn Pentilla

Lynn knew something was wrong when her daughter failed to call her on October 18, as Jennifer said. At first, Lynn was not worried, thinking maybe she was not near a pay phone or whatnot. But when Jennifer did not call on her birthday, October 19, Lynn knew something terrible had happened.

Jim and Lynn traveled to Deming, searched for Jennifer, and plastered missing person flyers across the town. They traveled New Mexico’s back roads for six days and stopped at bicycle and pawn shops. They never found any sign of Jennifer and eventually went back to Montana.

Deming police and New Mexico State Police did little, if anything, to find Jennifer after she disappeared until the day hunters found some of her belongings.

Eleven Months Later

On September 4, 1992, dove hunters traveling through Hatch drove down a dirt road two miles off Highway 26, across from the Las Uvas Valley Dairy, to find potential dove hunting spots. They found several of Jennifer’s belongings: her backpack containing two Bibles, Jennifer’s travel visa, and a journal, a bicycle helmet, a gray and blue tent, and Jennifer’s wallet.

The hunters called Hatch authorities to report the items, but they seemed uninterested. The pair then tracked down Jim and Lynn in Montana and told them of their discovery.

Police Investigation

After the discovery of Jennifer’s belongings, law enforcement finally began an investigation. They searched the area where the items were found but ended that search two weeks later and were unsuccessful. They did find a small lantern, a map, full baby food jars, and cigarette butts. Jennifer did not eat baby or smoke cigarettes.

At that time, investigators said none of those items had been sent to the crime lab and said there were no signs of foul play at the scene.

Once word got out about Jennifer’s belongings, witnesses notified the police. They said they had seen Jennifer with Jesus “Chuy” Vasquez, then 21, an attendant at the Deming Shell gas station, where Jennifer called her mother. Vasquez’s father, Henry Vasquez, owned the station, and he previously owned Henry’s Gulf Station in Deming.

New Mexico State Police Special Agent Miguel Frietzke, Jr., interviewed Vasquez on December 15, 1992, but you’ll never guess where the interview occurred – in his squad car with Vasquez in the back seat outside the Shell gas station.

Vasquez’s Police Statement

According to Brian D’Ambrosio of The Montana Review, Vasquez claimed Jennifer entered the gas station around 10 or 10:30 a.m. on October 17, 1991, and they briefly chatted about her bicycle.

Vasques told police the bike was “just a regular touring bike. I’m pretty sure it was white.” He also said Jennifer was wearing wool socks and hiking boots and mentioned “something about coming from Mexicali.”

He said Jennifer then exited the bathroom about five to ten minutes later. She purchased something, left the gas station, and walked her bike “heading east,” Vasquez said.

Vasquez stated that Jennifer mentioned “something about going to a travel agency” but made a call on the outside pay phone first. She spoke on the phone “for about 10, 15 minutes.”

But there’s a problem with his statement. Lynn’s telephone records showed Jennifer called her collect at 7:52 a.m., more than two hours before Vasquez said Jennifer entered the gas station.

Frietzke should have established Vasquez’s work schedule or when he arrived and left work on October 17, but he did not, for whatever reason.

Vasquez Subsequent Criminal Record

New Mexico State Police arrested Vasquez in September 1994 after selling narcotics to an undercover agent. Shortly after, Vasquez “suffered an accidental overdose” or attempted to take his own life. When police questioned him about Jennifer, he remained silent.

About a year later, Deming police officer Edward Apodaca wrote the Pentilla family, stating Vasquez’s ex-girlfriend noticed him wearing a leather bracelet similar to Jennifer’s friendship bracelet. She mentioned it to Vasquez, and he quit wearing it.

Another Suspect

While Vasquez seemed the likely suspect in Jennifer’s disappearance, another one emerged. A witness reported to New Mexico State Police that he saw Jennifer riding her bike on October 17, 1991, near the Hatch airport. A 1953 Chevy truck driving in the opposite direction turned around and headed toward the girl. How this person knew the year of the truck is beyond me.

An employee at Quick Pick Store in Hatch, seven miles from where the hunters found Jennifer’s belongings, was positive she saw Jennifer in the store with two men, “one stayed by her side, and the other stayed on the outside by the phone.”

Soon after, New Mexico authorities named farm laborer and Hatch resident Henry Apodaca a person of interest after he boasted about abducting Jennifer.

Henry was 37 in 1991. Police never charged him with a crime. He disappeared on October 10, 2010. Authorities found his body on April 8, 2011. The autopsy showed no injuries or trauma on his body that could have contributed to his death; however, police found drug paraphernalia with the body.

Weird Sh*t Regarding This Case

Here are a few things I find weird regarding Jennifer Lynn Pentilla’s disappearance.

No search for Jennifer or press articles.

I could find no information regarding any New Mexico law enforcement search for Jennifer between the day of her disappearance and when the hunters found her possessions a year later. The local newspaper, The Deming Highlight, failed to publish any article on Jennifer other than a blurb and mention in an opinion piece a month after she disappeared.

Why wasn’t the disappearance of an 18-year-old female taken seriously?

Vasquez’s police interview in Frietzke’s squad car.

It is unprofessional for a police officer to interview a potential witness or suspect in his squad car. I realize it was the last location where Jennifer was seen, but I find it odd. So, I wonder:

- Why didn’t Frietzke interview the potential suspect at the police station or Vasquez’s home?

- Did Frietzke know Vasquez personally?

I searched online unsuccessfully for Frietzke. It’s as if he never existed. The only thing I found about him was in D’Ambrosio’s news article.

Vasquez got away with murder, possibly for the second time.

In October 2011, Vasquez, then 41, beat his brother, Frank Vasquez, to death. He later pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter. D’Ambrosio states, “The defense contended that Frank was in poor health due to a number of ‘undiagnosed medical conditions and extreme methamphetamine intoxication.'”

The judge believed Frank died of a heart attack caused by the altercation with his brother and sentenced Vasquez to a slap-on-the-wrist punishment of four years in prison.

What???

Vasquez returned to Deming after prison but supposedly remained law enforcement’s person of interest in Jennifer’s disappearance.

In 2016, Officer Edward Apodaca wrote a letter to Jennifer’s family, stating he told Vasquez numerous times that Jennifer deserved justice and that her death “might have been unintentional or even accidental.” When D’Ambrosio contacted Apodaca for a statement, he refused to comment on Jennifer’s disappearance.

What caused Apodaca to leave DPD and his refusal to speak about the case? Did someone silence him somehow or threaten him? I found that strange, too.

LE not testing evidence.

D’Ambrosio states, “The cigarette butts and jars of baby food found in 1992 are not part of the list of inventoried items said to be stored at the New Mexico State Police Crime Lab, even though they were found with Jennifer’s belongings.”

Make that make sense.

As mentioned earlier, investigators in 1992 had yet to send any of Jennifer’s belongings to a crime lab when the search ended, which makes zero sense.

Similarities to the Tara Calico Case

Eerily similar to Jennifer’s disappearance is the case of 19-year-old Tara Calico, who disappeared in September 1988 from Belen, N.M., 200 miles from Deming. Any true crime fan knows about Tara, but if you do not, you can read my blog post, Tara Calico Disappearance and the Haunting Polaroid Picture.

In both cases:

- The victims were in their late teens.

- The victims disappeared in the fall one month apart

- The victims were riding mountain bikes along highways before they vanished.

- A 1953 pickup truck was seen driving behind the girls as they rode their bikes along highways. In Tara’s case, the truck was a Ford with a homemade shell, and in Jennifer’s, a Chevy; however, both trucks were similar in appearance; witnesses might have gotten the make wrong on one of them. Henry Apodaca could have changed vehicles because the crimes occurred three years apart.

I did not see a possible connection until I saw the “1953 pickup truck.” I’m not saying the two cases are related, but you never know. A new update in Tara’s case states the truck’s driver was in his late 30s or 40s, a white or light-skinned man with red or brown hair. So it probably was not Henry, but the two cases are too similar, in my opinion.

Aftermath

Jennifer’s mountain bike, friendship bracelet she wore when she disappeared, and blue and silver sleeping bag have never been found. Her aunt’s name was engraved on the bike’s underside. The bicycle’s serial number was F 9101771.

Jennifer had mailed Lynn a package while she was in California. It arrived after she disappeared. The envelope on the front partly read: “SOMEWHERE SOUTH.”

Sources

D’Ambrosio, Brian. “Jennifer Pentilla: A Montanan Forever Lost in New Mexico?” The Montana Review. April 4, 2021. https://www.montanapress.net/post/jennifer-pentilla-a-montanan-forever-lost-in-new-mexico

Good, Meaghan. “Jennifer Lynn Pentilla.” The Charley Project. https://charleyproject.org/case/jennifer-lynn-pentilla

“Parents and Policemen Await News of Missoula’s Jennifer Lynn Pentilla.” The Missoulian. September 11, 1994.