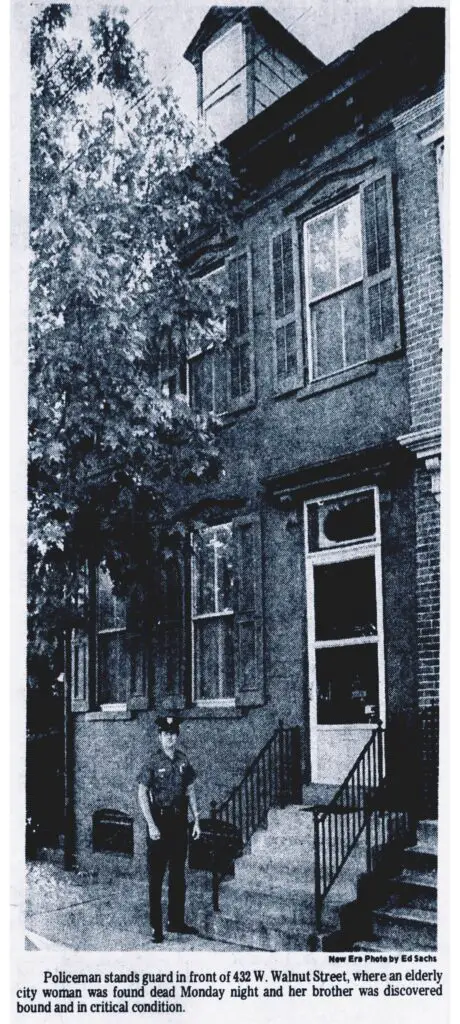

LANCASTER, Pa. — Elderly siblings Mary Amanda Swarr, 87, and Horace John Swarr, 81, had lived together for 30 years. Between 1959 and 1964, they purchased a three-story Victorian townhome at 432 W. Walnut Street, next door to the home they grew up in at 434 W. Walnut St.

The Swarrs had no close relatives in Pennsylvania. The only surviving relatives were nephews Charles Swarr in Reston, Virginia, and Frank Swarr in Louisiana. Neither sibling ever married or had children.

Mary Swarr was the former secretary of Pennsylvania congressman John Roland Kinzer from 1930 to 1947. When Kinzer relocated to Washington, D.C., Swarr stayed in Kinzer’s Lancaster office, working for his partner, the late Clay M. Ryan. She retired in 1971 at the age of 79.

Swarr was well-known and well-liked, hardworking, and generous. While her memory was lapsing, she still did her grocery shopping.

Horace Swarr was a self-employed electrician who learned the trade in its infancy. He was polite but feisty and always answered the door. But one day, he opened the door to the wrong people.

Around 7:30 p.m. on Monday, Sept. 17, 1979, Donald Moyer, a circulation manager at Lancaster Newspapers Inc, delivered a route for a carrier and became suspicious when he saw newspapers piled up on the front steps of the Swarr home. He tried opening the door, found it unlocked, and called the police.

When police officers arrived, they found Swarr dead on the living room floor and her brother beside her, barely alive. The siblings were bound with cords and blindfolded; Swarr was also gagged. Her brother had been struck above the right eye with a blunt instrument.

Both victims were lying face down, fully clothed, with their hands tied behind them. Their feet were not bound, but they were likely unable to move because of their ages, police said.

Dr. John Palumbo, a city deputy coroner, was called to the crime scene to declare Swarr dead. County Coroner Dr. Whitlaw Snow and Dr. Enrique Penades, a pathologist, accompanied him.

Swarr’s body was transported to Conestoga View, then Lancaster County’s hospital facility, and now a nursing and rehabilitation home.

An ambulance transported Horace Swarr to St. Joseph Hospital. He was able to speak with ambulance personnel and nodded his head when asked whether he understood what had happened. He succumbed to his injuries at 9:25 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 18, 1979.

Dr. Snow performed the autopsies and referred to the Swarr siblings’ deaths as “the most tragic situation” he had ever seen in his entire career. He determined both had died from dehydration and starvation.

Swarr had been dead for at least a day and a half before authorities found her body. As a result of not having food or water for several days, Horace Swarr developed bronchial pneumonia and blood clots in his legs. Adhesive tape covered their eyes and mouths, but no signs of physical abuse on Swarr.

Detective Joseph P. Geesey headed the criminal task force investigating the deaths. The appalling crime looked like a robbery from the start. The assailants had searched desks and drawers and scattered several items over all three home floors. It was evident to detectives that the theft had been pre-planned because the robbers had brought cords and blindfolds. Authorities seized the gag and rope as evidence.

There were no signs of forced entry, which suggested one of the siblings had opened the door and willingly let the perpetrators inside the home.

Investigators discovered an unidentified caller telephoned the police on Sept. 10, 1979, saying an elderly couple was tied up in their home. However, the caller mistakenly gave the wrong address — 442 W. Walnut instead of 432 W. Walnut. Police awakened the resident at 442 and found him unharmed. They dismissed the call as “unfounded.”

Investigators later said they believed the caller was either one of the robbers or someone who had knowledge of the robbery and called the state police so they could rescue the siblings but inadvertently gave the incorrect address. As a result, Swarr starved to death days later, followed by her brother on Sept. 18, 1979.

Charles Swarr arrived in Lancaster shortly after he received the news about his aunt and uncle. He told investigators they had previously kept considerable amounts of gold and silver coins in their home. Detective Geesey believed the robbers might have been after the lucrative coin collection, jewelry, stocks, and bonds.

The robbers had emptied Horace Swarr’s wallet and Swarr’s cash box in her bedroom. However, the robbers overlooked $4,300 in the home. Authorities found the money buried under papers on a desk in a second-floor room. The cash was mostly in $20 or smaller denominations. One detective theorized that Horace never deposited the lump sum into a bank.

Police found no trace of the large gold and silver coin collection in the home.

Detectives opened a Swarr family safe deposit box at Commonwealth National Bank a few days later but found no coin collection or will.

Police were uncertain if the Swarrs had an extensive coin collection in their house at the time of their deaths. A relative last saw the coins in 1976.

About a week after the deaths, city detectives tried locating two women seen eating lunch with the siblings, possibly on the day they were robbed.

Between 40 and 50 years old, the women were seen with the Swarrs around 2 p.m. at the Dirty Ol’ Tavern at Engleside, possibly on Monday, Sept. 10, 1979, or the previous Monday, Labor Day.

The women were laughing, and Horace Swarr even cracked some jokes. Police said it was likely that “these two women knew them and possibly might have been good friends.” Authorities urged the women to come forward, but they never did.

Detectives also spoke with the Swarrs’ physicians. Dr. James Fatta, a podiatrist, said he had been treating Swarr, while Dr. Charles P. Hammond recalled treating her years before. Dr. Fatta knew the siblings and said Horace Swarr was remarkably fit for his age and might have been physically able to put up a fight against the robbers.

The investigation into the Swarrs’ disturbing deaths eventually fizzled out, and the case went cold for a decade. Then one day, investigators made an announcement, and by the end of January 1989, they had arrested four men for the Swarr murders.

The suspects were from Maryland. They heard through the grapevine that the Swarrs kept much cash and valuable coins in their home.

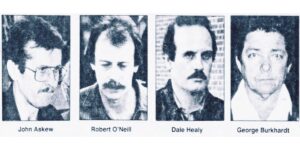

Police charged the following men with two counts of criminal homicide and conspiracy:

- John Arthur Askew, 51, of Princesse Anne, MD

- Robert Paul O’Neill, 40, of Finksburg, MD

- Dale Healy, 45, of Baltimore, MD

- George W. Burkhardt, 51, of Upper Falls, MD

Authorities acknowledged they had seized a Levi “Wildfire” brand brown business suit, size 38 regular, worn by one of the suspects to the Swarr home.

According to the police, one of the men dressed in the suit knocked on the Swarr home door, posing as a Social Security employee. Once inside, the robbers bound and gagged the elderly siblings, stole whatever they could find, fled the home, and made an anonymous phone call to the state police.

The robbers most likely fled the home through the side entrance facing Lancaster Avenue.

The significant break in the case came in November 1987 when O’Neill’s wife, Denise O’Neill, told Baltimore County police that she had information about the botched robbery. Subsequently, Deborah Denise Snyder and Lawrence G. Snyder, a Baltimore couple who shared a home with the O’Neills in 1979, told detectives they saw O’Neill dressed in a suit, and Askew had visited their house with O’Neill.

According to court documents, O’Neill told the Snyders he and Askew planned to rob someone dressed as insurance salesmen to gain entry into the victim’s home.

O’Neill told the Snyders the following day, “We committed a robbery in Pennsylvania, tied up old people.” O’Neill was upset because he only got a few old coins, which he showed the Snyders. He also said the phone call was meant for the police to find the Swarrs, but they were not discovered in time and died.

Maryland and Pennsylvania detectives began working on the case and asked the Snyders to wear a wire to record the conversation. The Snyders met with O’Neill on Jan. 12, 1989, in Finksburg, Maryland, and during that discussion, O’Neill described in detail how he and the other men committed the crime.

Per affidavits obtained by the Intelligencer Journal:

“O’Neill and others went to Pennsylvania in the center of the city, posing as insurance men, tied up the old people, laid the woman on the couch, and, before they left, told them that someone would come for them.

“They left, and he, O’Neill, made a phone call, but the police never arrived. O’Neill said he discovered that the older adults had died from newspaper reports.

“Askew was responsible for setting up the robbery; Askew knew and obtained two conspirators who participated in the theft, including a conspirator who entered the Swarr home with O’Neill; Askew stayed outside in the van; afterward, Askew was furious with O’Neill for the failure of O’Neill to communicate the address to the police correctly and threatened to kill them.

“Askew and/or the other males bought Venetian blind cord to tie the victims; O’Neill, and one of the other males, entered the Swarr home and Askew remained outside; the Swarrs was gagged, tied, their house ransacked and several coins, currency, and bonds were taken; Askew gave O’Neill the Swarrs address so O’Neill could notify the state police at Lancaster; the proceeds of the robbery were divided in Askew’s residence.”

Police obtained a warrant the next day for O’Neill’s arrest, and Maryland police apprehended him on Jan. 14, 1989.

At a preliminary hearing in February 1989, O’Neill testified that Askew asked him to participate in the robbery and that the four men planned the crime in a local bar.

O’Neill said he and Healy had to gag Swarr after she managed to untie her hands and scream for help. He admitted he was the one who made the anonymous call to the state police and mistakenly gave the wrong address.

O’Neill also stated that Swarrs’ nephew told the robbers about the coin collection and stock certificates. They made off with a large can of old coins and some stock certificates and then returned to Askew’s home, where they divided the robbery proceeds. The four men split the coins, and Burkhardt took the certificates.

Trials began in September 1989, starting with Askew, the prosecutor dubbed the “ringleader.”

Askew denied being the ringleader but admitted to recruiting the other three men who committed the crime. He said he also relayed messages between the participants but was in Maryland during the robbery.

His story conflicted significantly with O’Neill’s testimony, corroborated by the tape-recorded conversation between O’Neill and the Snyders.

Askew said he met O’Neill during the summer of 1979 when O’Neill rented a room at the house of a friend, Jim Ward. Ward asked Askew to give O’Neill work by letting him assist on his beer delivery route, and he agreed.

According to Askew, O’Neill asked if he knew of an easy target to rob because he had financial difficulties. Askew explained that another acquaintance, Donald Wayne Nelson of southern Lancaster County, had recently tried to recruit him to steal from the Swarrs.

Nelson had learned about the Swarr’s coins and money from a nephew of the siblings. Askew then passed the messages on to O’Neill, who ultimately carried out the plan with Burkhardt and Healy.

Healy’s trial in November 1989 revealed that Healy wore a wig and posed as a Social Security agent to gain entry into the Swarr home.

Burkhardt, awaiting trial on the exact charges, was ordered to testify at Healy’s prosecution or go to jail but feared self-incrimination. He finally testified after Judge Michael J. Perezous ordered him to do it.

Burkhardt attested that he was the getaway driver. He drove to Lancaster in September 1979, unaware his associates were planning a robbery. He learned what happened following the theft and stayed silent because he feared for his life.

Three suspects were ultimately convicted and given life sentences. O’Neill pleaded guilty to third-degree murder and received eight to 20 years in prison, rumored to have resulted from a special deal with prosecutors. He was released in 2001 and returned to Finksburg.

The remaining three have unsuccessfully filed appeals over the years. Askew and Healy are still in prison. In 2021, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf commuted Burkhardt’s sentence to “life in parole,” Lancaster Online reports.

In May 1994, 15 years after the Swarr murders, police arrested “middle man” Donald Wayne Nelson, 58, in Galax, Virginia.

Nelson was a well-driller who had been romantically involved with Ann Swarr, now deceased. Ann was the Swarrs’ niece by marriage to Charles Swarr, but the couple was estranged.

Charles and Ann’s son, Gregory Swarr, told Nelson about the coin collection while Nelson was dating Ann. He was a teenager at the time.

Authorities interviewed Gregory Swarr in November 1993, then 38 years old. He said in 1976, while working for Nelson, he had bragged about the Swarrs’ wealth to impress Nelson.

“I was trying to boast, hoping that (the relationship) would work out,” Gregory Swarr said.

Gregory Swarr also admitted to Detective Geesey that he and Nelson drove to Lancaster to burglarize the Swarr home in 1976. But the Swarrs stayed in their house that day, and Gregory Swarr changed his mind and wanted to go.

On the way back to Maryland, Nelson said he would return at another time to rob the Swarrs.

Defense attorney Howard Knisely asked Gregory Swarr what he had received from the Swarrs’ estate after their deaths.

“I got guilt out of it,” he tearfully replied.

Nelson pleaded guilty in April 1995 and received a five-to-ten-year prison term for conspiracy to commit burglary under the terms of a plea deal. Authorities dropped two criminal homicide counts against Nelson as part of the plea bargain. He died in 2014.